Thoreau and Luigi Mangione and Ives

I tried to write a gay essay on Ives and this is what happened

The rhythm of my typical day is simple. In the daytime, I emit content; at night I consume it. Maybe consume is not the best word for a semi-prostrate surrender to streaming video, on an ill-chosen sleeper couch.

Many things bother me about this pattern of living, aside from the couch.

One qualm has to do with beauty, the way that beautiful bodies appear at the cold click of a button. It’s not quite porn, but porn-adjacent. I don’t agonize a lot about this—only a bit, and half-heartedly. But occasionally I get a deeper guilt, a cynical ache about the way in this world most Good People are beautiful and most Bad People are not. Take Dune, easily one of the worst offenders—the Baron-villain has to be hideous, disfigured, enormous. (In the first film, Lynch goes heavy on homophobia/pedophilia, complete with oozing pustules of unspecified disease.) Atreides father and son are both ever so handsome and slim and heterosexual—and therefore noble. Jessica is gorgeous, naturally.

Just as bad: that show about the lavender scare (Fellow Travelers), which purports, like Dune, to be a moral fable. An absurd festival of cut abs and lasered chests and rakishly handsome smiles, sprinkled with a few adorable token lesbians. In the evil corner you find Roy Cohn, who looks awful. They wrote a Origin Story Scene which neatly and tightly tied his facial deformity to his moral failure.

This coupling of physical beauty and morality is ugly. It is insidious and corrosive. We put up with it all the time, and I’m sure (like other market-driven algorithms) it wears away at our resistance. Some people are willing to go to the mat for inner beauty or moral beauty but many people want their heroes and heroines to be gorgeous and their villains to look terrible, either just balding and sad, or almost at the edge of human, like orcs1. This makes it all much easier to keep track of.

—

This week, as I went after the “Concord” Sonata one more time, I had to ask a perennial Ives unanswerable question: how ugly should I play it? This is not a joke. It is an almost moral question. I don’t think Ives usually set out to be ugly—not for ugliness’ sake. But the question of too-easy beauty bothered the hell out of him.

It surrounded him, in the form of music American composers were writing at that time, channeling Wagner and Debussy but without quite as much integrity of conception. In a lot of this music, you get the feeling of floating through a decadent, pleasant, well-lubricated harmonic soup (but not too floaty, not so much as to make people freak out!) This kind of beauty was woven with class and society and a certain kind of classical aficionado (which still exists) for which Ives had absolutely no patience, and did everything in his power to antagonize. He was part of that privileged class, and could have slipped into that world easily, except that he didn’t, couldn’t, and/or wouldn’t. He resisted. Resisting this kind of beauty was also resisting that world, and its whole system of taste.

Everyone’s done a lot of work unpacking the toxic masculinity angle of this. Good job everyone! But Ives’ misgivings about beauty were broader and deeper, and I’d argue his solutions were profound.

—

Ives wrote some of the most beautiful American music—at times, passages of jaw-dropping, seductive refinement. I mean, just listen to the beginning of the great great great DeGaetani-Kalish performance of Housatonic at Stockbridge, a touchstone:

At 1:20, you literally get the words “how beautiful!” As we naively name beauty, the music slips into the groove of a whole-tone scale, and veers dangerously close to raw Debussy. The French sense of color is woven into this song, no question.

But what makes this song such a masterpiece is a kind of shotgun wedding of styles. A meeting point for three seemingly irreconcilable notions/systems of musical beauty. First, the hymn, and all of its chaste, religious associations, the simple triads passing from one to the other, the leading voices, the well-worn, homespun cadences—if you will, no sex before marriage. Then a more promiscuous, late Romantic, early Impressionistic harmonic environment—a world where these triads and their hierarchies no longer have as much power, lush and sensual and fluid. Finally, an unknowable, unsystematized cluster world, with craggy vast harmonies that appear out of nowhere, superimposing themselves on the rest—this evokes a sense of the infinite (asexual?) These ideas of beauty meet each other at various boundaries in the song, and melt into each other, and—you have the sense—teach each other something.

The way Kalish plays the last bars: holy crap.

—

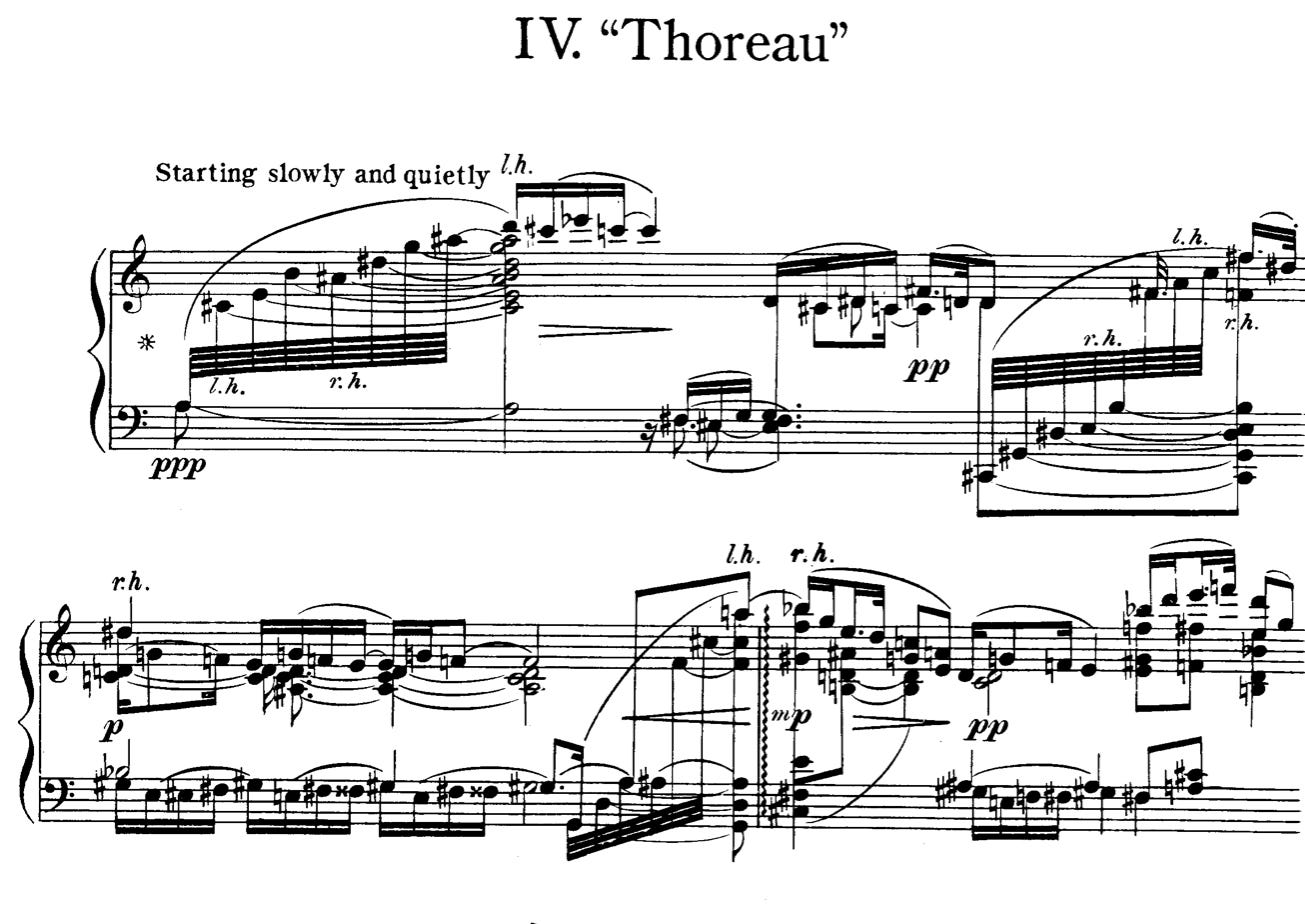

At the beginning of Ives’ portrait of Henry David Thoreau, we find ourselves also (curiously) in a French-adjacent musical world:

More than a bit of Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun in there! (But if you read Thoreau a certain way you find a lot of proto-Proust.)

The opening arpeggio consists of two chords: A major, and E-flat major. They are a tritone apart, an “ugly” interval. Many classical musician geeks will quickly identify this particular bitonality as belonging to Stravinsky’s Petrouchka, e.g. the well-known clarinet moment:

In the Stravinsky, the effect is cheeky, ironic, a bit of puppet caricature. Here, Ives is after the opposite of irony, a gauzy beauty, combined with distance, mist… a morning, where things are not yet truly seen, where everything is yet possible.

In Ives’ arpeggio, however, there is one renegade note, that cannot easily be explained: a B-natural. It belongs to neither chord, yet somehow serves as a link between them. A chromatic line whose origin or destination are unknown. This note says “screw you” to the analyst, and spoils the perfection of the musical structure (one form of beauty) in pursuit of something else. This is the quintessential Ivesian note.

At the top of the arpeggio, Ives unfurls a little cluster:

Clusters are not everyone’s favorite, of course; they are in a way the nemesis of conventional musical beauty. A toddler’s careless hand on the piano bangs out clusters, or the cat walking up the keyboard—clusters are a joke, a mistake, a mess.

Ives spells out the cluster, one note at a time, so that you can hear all the chromatic individuals that make up the little mess. The notes are so close that sorting them is tricky; they melt and blur. In the process of the next minute we keep listening to this cluster, and other similar clusters … a clustering of clusters.

To call this clustering harmonic ambiguity is somehow to buy into the realm of conservatory musical analysis—I’m not sure Ives wants us to do that. As the next minute of music unfolds, fragments of melody grab onto one note or another from these clusters, and you can be forgiven for wondering for a moment, this is the main note?, this could be the key? These little attempts at navigation are bound for failure. I’m not sure the question of what key this is in should even come up. You feel—as this passage goes on—that the cluster is the key. A cluster cannot really be a key. You can’t say a piece is in the key of splat! And yet …

The un-beautiful object of the cluster is the thing Ives wants us to truly hear, and come to appreciate as beautiful.

—

Because a single note at the piano always decays, there are many stratagems for making notes richer and bigger, delaying or concealing this unavoidable mortality. Basically—plastic surgery for piano notes.

One of the most common is the octave, a way of deepening and doubling a sound. This hack has been around forever, a stop on the organ, coupling on the harpsichord, and of course the octave becomes a fixture of Romantic piano virtuosity, climaxing in stuff like this famous passage from the Tchaikovsky Concerto:

For Ives, this kind of posturing was his worst nightmare, the masturbatory reflex of an overheated aesthetic, and the Late Romantic Octave represents a kind of existential problem. He needs a way to make his melodies sound rich and singing at the piano—to get an orchestral sound or an organ sound, a density, a depth—but he doesn’t want to double, because it’s too easy, too formulaic, too boring.

The more you play Ives, the more you realize that his solution was to “diversify” the octave. When he writes a minor seventh:

that is often an octave, in meaning. And so too for the “uglier” major seventh:

Or a ninth… things that are close to octaves. In many normative circumstances, these might be heard as a missed note, a slip of the finger. But for Ives all of these things are in a way “truer” octaves, more real doublings.

As you let yourself into this style, you begin to agree with Ives—and you wonder if you’re going insane. You begin to think that these sevenths and ninths sound better or deeper than actual octaves. Octaves begin to sound insipid or empty. The grind of the “wrong” note comes to feel like a kind of color or resistance or grit within the idea of a single note. Alternative octaves allow him to have his cake and eat it too. They contain both the jangle of dissonance plus the meaning of unity.

Elliott Carter sniffed at this—he accused Ives of adding dissonances cheaply, willy-nilly. For certain schools of composers, an octave is one thing and a seventh is another, and to switch them out for each other is a loss of musical integrity, a betrayal. But I feel like he’s applying the wrong value system. And anyway, many composers try to make certain chords “feel like” other chords; Wagner tries to tell us that dominants are actually tonics; Beethoven famously makes the tonic chord sound like a giant dissonance in the opening of the Fourth Concerto; so much of the memorable music we love is about redefining the terms of engagement, the terms on which music is heard.

Again and again, Ives gives us an apparent antithesis of beauty, which turns out to actually deepen the beauty. He keeps daring us to come through that process with him. Much has been made of the way Ives recreates the ideal, fervent musical world of his childhood. His music is indeed a kind of memoir, an attentive act of cultural memory. But I wonder if this is the even deeper insight for him—this turning inside-out of the beautiful.

—

On the plane to Tucson, I was trying to read, or at least give the appearance of being virtuous and consuming a book, but I had to keep some fraction of my brain busy with some BS content (House of the Dragon), so it could quiet down enough to follow the sentences. This ridiculous strategy (a sign of terrible addiction) actually worked for a few minutes! I had completely lost myself in a historical novel when a slithering in my headphones made me look up.

I saw a burned torso bathed in red shiny blood, and the caption

[PUS SQUELCHING]

Really? For a moment it seemed impossible to live in a world with this subtitle. My puffy-faced neighbor appeared unfazed. He didn’t hear the sick liquid sound in his ears, like I did. The word squelching made the sound so much worse, somehow. Couldn’t it just have been blood? why specify pus?

I munched on SunChips for consolation. The aggressively un-beautiful, everywhere, filmed ever so beautifully—murders, gruesome wounds, people burned alive by dragons or raped or tortured on racks, the endless gun porn, the way the characters in The Matrix are at their sexiest when they’re arming themselves with ridiculous amounts of automatic weapons, for instance, and incalculable scenes savoring the slow-mo of bullet casings falling to the floor, or Uma Thurman slicing limbs off of brightly costumed kung fu minions, or beautiful people slaughtering hideous zombies in post-apocalyptic scenarios with shotguns and machetes, or tormented American snipers killing desperately poor brown people from unspecified countries, with sad handsomeness in their eyes and a pious pretense of if only I could have mercy for the cameras … I suddenly felt, there in the plane, squeezed and squelched not by my neighbors but by content. Too much violence available, on top of too much beauty, and too much easy conversation between them.

Sure, this isn’t new. Cast your mind back to Lear or Titus Andronicus or Dante or the Bible or Homer or Greek tragedy and this exploitation of violence for beauty (and vice versa) has been around, a crucial part of human myth-making and story telling and a way to make sense of the violent beautiful world. But doesn’t it seem extra-concentrated and extra-gratuitous right now? Speaking of which:

—

In the middle of “Thoreau,” Ives gives us (and himself) a classically beautiful moment. Thoreau has been rousing himself out of the mists for some action. A few simple chords take us out of the clusters

(Listen to these chords emerge)

A still moment of clarity. Then, some ambition takes over (he is a dude, after all): a “getting goin” passage.

A second time, we stop, get going. Ives is making us participate in a long process of patience vying with impatience.

A third time, now, we stop—and this time, as we “get goin” something unexpected happens. The A and B-flat alternating in the bass climb to C—it’s as simple as that. And we find ourselves in a passage of tremendous excitement and radiance:

C major, free of doubt—an astounding flash of light, after all the clustering and mists. The left hand, with little eruptions of rhythm, adds notes to our major chord—an F-sharp, a B-flat. In a textbook these would contradict the overriding harmony but here they are blue notes, confirming and adding joy to it.

I always get so terribly nervous here!, like when you’re talking to someone you have a crush on, when you don’t want to say anything wrong, or do anything stupid. These are some of the few wrong notes in the piece that have to be exactly right, at this moment that one half of the piece, with its beautiful desires, crashes into another, and its different desires.

That renegade F# rises to renegade B-flat, a climax, which shoots us beyond the C major to the other side of the circle of fifths, to F major. This is, for Ives, an unusually old-school functional Classical-music-maneuver, a Mozart and Beethoven standby. You’re headed for the tonic. You’re about to resolve by fifth in the bass like all the good Classical music pieces do. But at the moment of final settling you overshoot, and descend one more fifth

G ——> C

could be done and done … but no, wait!

G——> C——> F

To put it in baseball terms that Ives might appreciate, you’re sliding into home, and you end up in the dugout. This appearance of the subdominant F at the eleventh hour is most often a transcendental trick, to pass round and through one’s desire to a place even further within, even further from tension, even further released.

You can see this idea of release embodied in the right hand, those falling Ds to Cs:

But in the left hand something new has started, an etched ostinato. One hand lets go; the other crystallizes. The old thing is falling apart, letting go with great feeling, in an F major that is already becoming a memory, and the other thing is there to hold us up as we let go.

A more perfect climax rarely exists in Ives (or anywhere). For those bars, at the top of the printed page, “Thoreau” is more or less paradise. It’s so perfect and blissful, of course, that Ives has to spoil it:

Goddamn it! Ives does this so much. At the end of the First Violin Sonata, as the clanging bells die away and the hymn too, and you are left with just a gospel Amen, and a murmuring tremolo in the violin, you hope that Ives will just let you have this one nice moment, just once, so you can let the audience go home bathed in a reverent F major, with only memories of past dissonances. But no! in the last measures, Ives writes this off-key, off-rhythm fragment of something unrelated:

Lest you be tempted to play it too beautifully, as a kind of vaporous after-echo or dream, he writes a pointy wedge on the last note, haha, no, he says, screw you again. In the recording I cheat a little:).

—

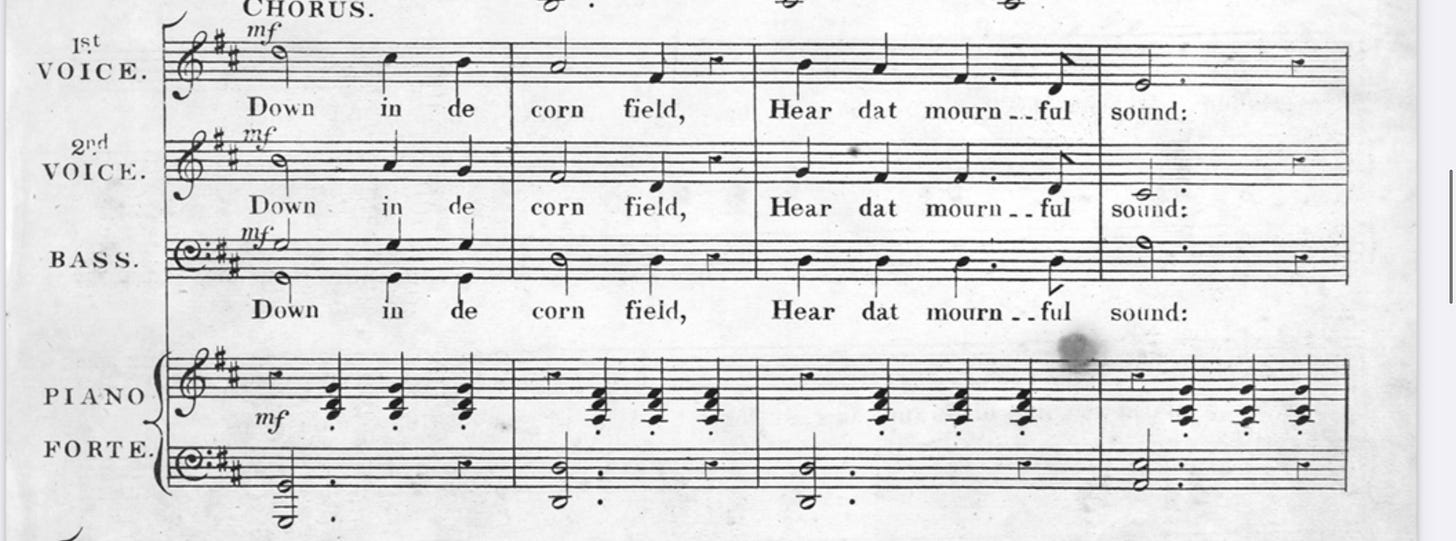

The spoiling of Thoreau’s beautiful arrival is also beautiful—and fraught, and dark. Ives takes us to one of his go-to Foster tunes:

The title—ugh, too racist to print. The song is a lament, the imagined mourning of an enslaved person for their owner: a disgusting trope in a demeaning dialect, a moral evasion of the ugliest kind. The musicologist Denise Von Glahn wonders how it is that Foster and Ives, both fervent abolitionists, could find this sentiment acceptable or worth expressing.

The reasons for this particular fragment in this essential slot of the “Concord”? I’ve heard three explanations. One is simply that it was one of his father’s favorite tunes, which reappears at defining moments. A haunting, a visitation, a seance. This is a compelling, likely possibility, but proof seems elusive.

The second explanation is a small word association. Thoreau said he “grew in those seasons like corn in the night” and the word corn brought the familiar Foster refrain to mind. Quite possible! A bit of randomness, a stream of association, is always part of Ives’ master plan.

A third fascinating possibility is offered by Von Glahn and her colleague the cultural geographer Mark Sciuchetti:

… we turn to a lesser-known history of Concord that the naturalist author reveals in chapter fourteen of Walden titled: “Former Inhabitants; and Winter Visitors.” Here Thoreau illuminates what is most often missing from celebrations of Concord, and absent from most Americans’ understandings of the place: the remnants of enslaved peoples’ presence …

In eleven pages Thoreau describes the historical habitations of three ex-enslaved people who lived in Walden Woods—Cato Ingraham, Zilpah White, and Brister Freeman—and more recent inhabitants, including the outcast Irishman Hugh Quoil.

Could be? Ives was extremely familiar with Walden. And however horrendous and morally blind this seems now, Ives (in other works) used this tune to evoke sympathy for people of color, to give them a voice within musical landscapes. You do have a sense at this place of a haunting, again, a lost and sad voice from the past floating through and against the radiant present that Thoreau had just found.

—

Ives’ treatment of Foster has two eloquent reversals. The D gets drained of its brightness, into a darker D-flat. Ives also turns the harmonies backwards. “Down” should be on the IV chord and “cornfield” should be on I, a good old fashioned sentimental “Amen” cadence. But Ives puts the tonic on “Down” and a somewhat ugly IV on “cornfield”, creating a deliberate problem chord:

Tricky to reach, among other things, and to voice. Whatever you might say about the quote of this song, then, it is not uncritical. It is based on doubt and displacement.

He only uses five notes of Foster. From there he extrapolates an “original tune.” This tune is symmetrical. The first five notes get a reply—an even darker reply!—sliding into the chromatic world of the classical lament:

Tropes of sorrow, including the accented, sighing inner line. This is the first real sadness in Thoreau, one feels—just after the moment of greatest elation.

Now Ives repeats the rhythm of “down in the cornfield” but substitutes in a yearning upwards phrase. We are still in mourning mode (that G-flat!).

But the last part of the melody does something we could never expect, five glorious downward notes:

This last five-note idea is immensely more hopeful than the first. It calls back to the rapturous climax of Emerson and the opening of the piece and many many other places. It negates the G-flat. The darker D-flat is reinterpreted as C#, and then is given two possible paths out… first, up to D, then down to C. A way out of this darkness.

Immediately, of course, Ives visits this hopeful cadence with a dark echo—salvation is never easy in his world:

Take a look at all the parts of this theme. Many of its chords have Ivesian alternative octaves in them, sometimes more than one at once. You see all kinds of awkward motions—tritones, voices out of nowhere, leaps that ignore all the niceties. An absolutely pivotal juncture in the “Concord”: a chorale that questions all the conventional beauties of chorales, that juxtaposes hope and sorrow, and merges a sentimental fragment of melody with its ugly, ugly American past. How much more do you really want from one musical moment?

—

I used to refer to a certain kind of Rachmaninoff passage as “afterglow”—post-coital bliss. I realize this is inappropriate, and not usable with students, even though I can’t for the life of me think of a more perfect image.

I’m really referring to the movie version of afterglow (Rachmaninoff provides movie versions of life, I’d say, more than life)… an often filmed moment, a coy after-the-fact euphemism for sex, of pulling out the cigarette from the nightstand, and basking in pleasure and regret. It’s such a black-and-white moment (even the anachronism of the cigarette). In Rachmaninoff you can almost hear the smoke drifting towards the ceiling, the pan of the camera, as he speckles his retreat from a climax with many chromatic, usually flat notes, gorgeous regretful brooding nuances.

Rachmaninoff usually brings us down nice and slow, wave by wave, layer by beautiful layer, to paint a complex picture, the beauty of unfolding and achieving and releasing and loss. It is one of his signature achievements. One of Ives’ signature achievements, also, is the after-passage. But a different kind—almost comically different in its values.

The “Concord” ends with a long come-down. The first sign of the true ending is the appearance of the flute, Thoreau’s flute, heard across the pond:

Just the sound of it is a relief—the beauty of its timbre against our long suffering with the piano sound. There is also the beauty of the reappearance of a beautiful theme, and the sense of coherence, connection, the story “making sense.” Completion, coherence, connection: all conventional beauties within the classical music value system.

But the piano is subtly working both with and against the flute, and the flute vanishes without quite finishing. Several problems hover around the simple beauty of return. Then the piano has a long epilogue, where fragments pass through the mind. Foster comes back again, with all its baggage, and then the hopeful five notes, and the dark empty echo, then the neutral mists again, ah nature, and way up in the stratosphere, as my wonderful teacher Peter Burkholder suggested, one last attempt at Beethoven’s Fifth:

(Listen to the end of Thoreau)

… just four chords, now, the canon reduced to blank chords, not rapping or knocking but gently pulsing, the stormy pitches have somehow been erased or dulled or eroded into this luminous last hint (is it or isn’t it?).

This is beautiful and of course sad, the erosion, the loss of specifics. It’s ambivalent—but not in a Schubert way. It’s uncanny like Schubert, but not so personal. Ives keeps gesturing towards the universal; he keeps panning the camera out. Because of this, you get more of a sense that beauty won’t quite adhere to a moment, a person, unrequited love, an experience, a harmony, a nation, anything. You become more aware of how it likes to attach itself to anything and everything, to different styles and perspectives—it is slippery.

Rachmaninoff was infinitely better at working within a conception of beauty. He is happy to build on it, comfortable with its foundation. Ives, less gifted in that way, felt that beauty was less reliable, less comfortable. It should “bother” you, like ugliness does. In that sense, you could say that Ives had a better understanding of beauty than Rachmaninoff.

Speaking of orcs—if I may put on my rampantly gay hat for a moment—I wish they had humanized Sauron as a hot leather daddy, which would make the series more morally complex, and explain his obsession with hobbits.

"I wish they had humanized Sauron as a hot leather daddy, which would make the series more morally complex, and explain his obsession with hobbits."

--gives the "eye of Sauron" a hole new meaning...

“if you read Thoreau a certain way you find a lot of proto-Proust.”

Yes