To make myself ready to play (this takes 95% of my time, and doesn’t always work as intended), I went to the gym in Marylebone. You step through space-age pods after entering a number—two dehumanizing steps—and are ejected into a habitat of mostly men in midday workout routines. Some are gung-ho verging on insane. Some spend a half hour standing still on a treadmill, looking at their phone. Others chat with other manly men friends, leaning on machines and piles of weights, as if posing for a photo shoot in the magazine Gym Life. The lighting is dim and concealing, like in a restaurant, but not atmospheric. I’m not sure a pianist belongs here. Where should a pianist work out?

Sweat accomplished.

Back out of the pods, in fresh air, the first thing I see is an elderly Asian man alone in a wheelchair. His eyes give no hint of seeing me, but I feel like he sees something, in the distance. His face looks smoothed and shiny, as if buffed. What he’s doing there on this sidewalk, helpless, in the frenetic middle of London? A wave of pity and a selfish pang of fear about my own aging (who will take care of me?) and then I see he is not alone. There are two oldish women, circling around him, stooping down in an odd birdlike way. It takes a moment to realize they are picking up red maple leaves that have shaken off a tree on my first blustery day in London. The red, on the gray. They are collecting delicate leaves off this soulless sidewalk, while the man they’re caring for sits and waits. In the post-gym combination of loneliness and endorphins it feels really moving, these paired forms of care and attention.

I cross Marylebone Road with some risk of death by moped, to find a large party on the far side. They’re in fancy ball gowns and rented suits, celebrating an event on the steps of a business school, all strewn with flower petals. The universe seems to be sending me a message, something about plants discarded on the ground. The well-dressed people dawdle and chat, there, with cars roaring past, and exhausting honks.

I find London far more tiring than New York, at times, more overwhelming, especially on a concert day. Don’t you all know I have to play the piano? I wonder and couldn’t you all calm it down. But the world seems only to get more intense once you begin thinking that way.

A bakery for afternoon coffee—there too the soundscape was clattery, edgy. Why so much in the world? I risked sharing my mind with the appealing, unusual-looking person at the register—“loud today”—and she looked over at a corner where two picture-perfect blond toddlers were whining, despite their identical felt pumpkin baskets loaded with candy. The children had a picture-perfect put-together mother who was buying them baby cappuccinos. They kept screaming at every injustice, a candy that was first given to the other child, a candy that was not the candy they wanted, the lack of a baby cappuccino (it’s coming), etcetera, and the world was not enough for them. (Trump voters, I thought.) There would be a brief moment of peace where the last want was appeased, but it was very brief compared to the moments where the next desire was so intense that they had to fight about it. Isn’t that a lot of world history?

In the music of Fauré, which I’m in London to play, you find opposed forces. First—I don’t think you can deny this—comes the pleasure principle. I mean that wonderful French capacity not to let a moment go by without something delicious to taste. Endlessly gorgeous seventh chords, each sliding or resolving through some French logic to the next.

But as you’re working with this music—and I especially don’t think you can deny this—you feel another force, which goes by many names, sometimes elegance, or taste, or a kind of savoir-faire, a distance, or just the rigors of structure, counterpoint, etc. This part of the music resists yielding to pure emotion, rapture, or release. It tells you, not too much. As you play you keep finding that surrender doesn’t quite do it. The music is full of traps, alluring sirens. So many points where you just want to stop—no, listen, let’s stay here on this island of gorgeous harmony—yet it keeps going on.

One classic and astounding example: the last movement of the C minor Piano Quartet.

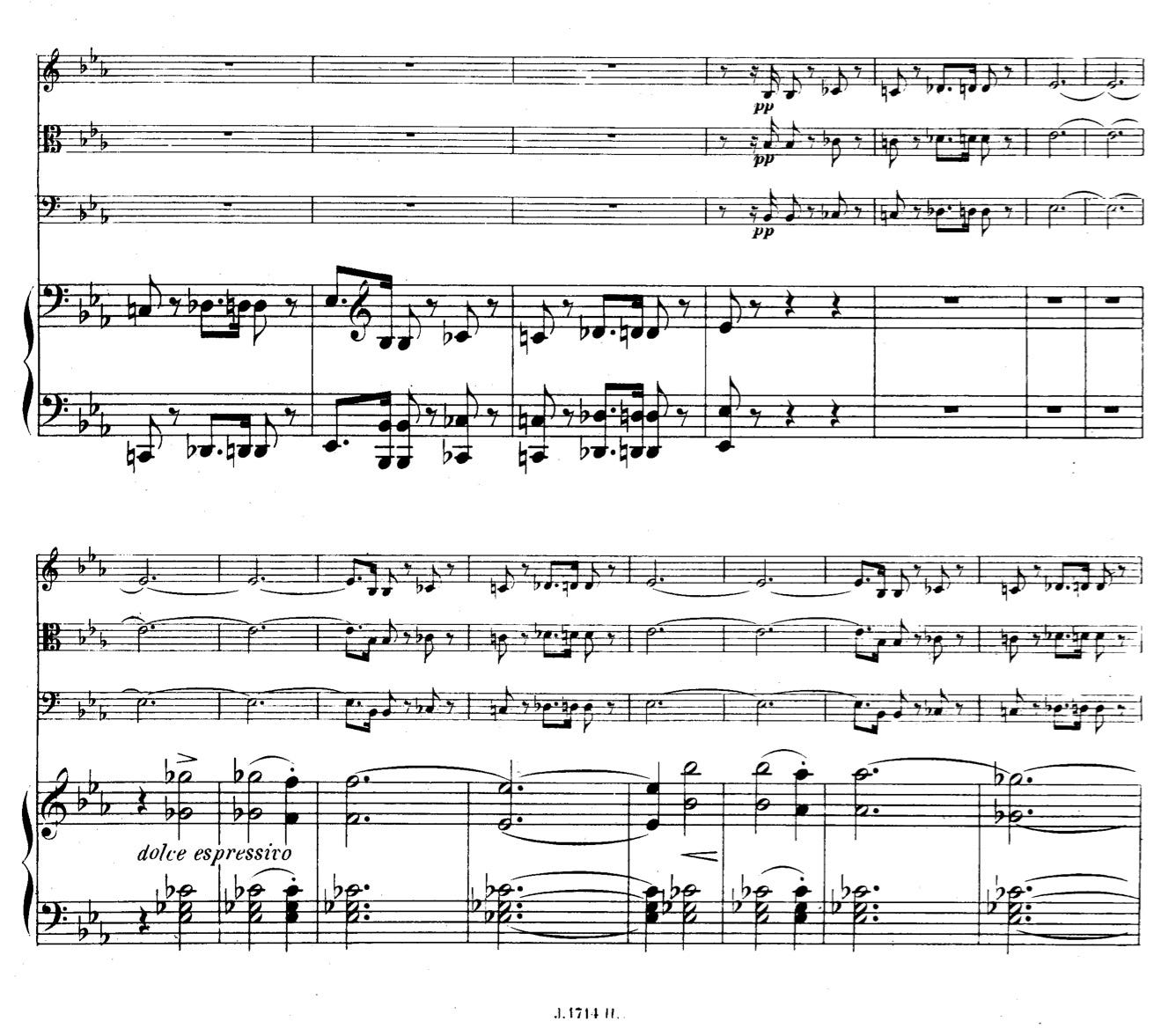

The piece comes to a seeming standstill and into this emptiness the piano inserts an enigmatic (but highly expressive) melody, or a scrap of a melody, really—just three notes with a dissonance in the middle:

There is beauty here, but it is partial, austere, a beauty in some ways about absence, about what is implied, about waiting, about harmonies that are not fully explained.

Then come two phrases where it gets tested out, the idea. A rustle of harmony helps, filling gaps. A waltz, maybe?

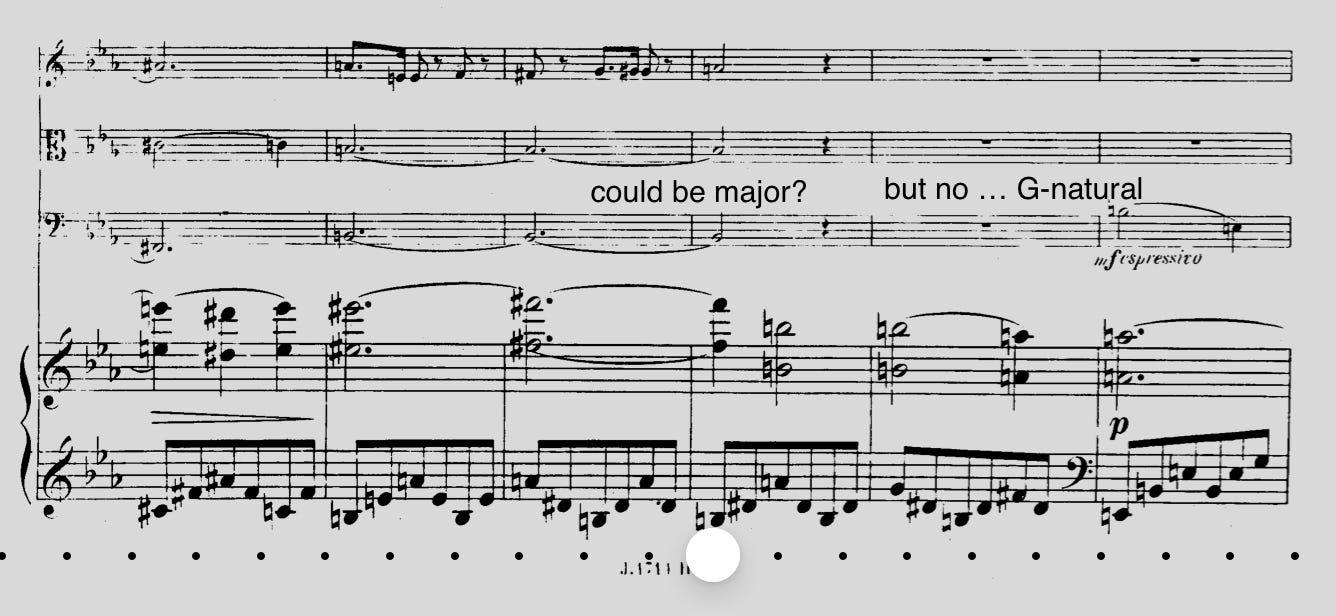

The harmony drifts into the major, becomes more nurturing, more lush … Maybe it will be C-flat major, you imagine, but it never comes, and we switch over to maybe E major, which also never comes, because in the great inflection point of this magnificent development section, the major now flickers into minor.

Before you have time to process this sea change, and seemingly as a result of this sudden melancholy, the enigmatic piano theme discovers its own apotheosis.

In the wake of this evil election, yes, it seems silly to rhapsodize about this rush of beautiful notes. It must be confessed that when we played it just now at the Wigmore, I never spoke up in rehearsal about this place. Our account of that moment that night (I thought) lacked special sauce. (I could be wrong? You can listen here. I thought the Trio from night 4 was pretty good, and the D minor Quintet night 2, C minor quintet night 3, and “Dolly” from night 5.) We were like that group in their fancy outfits on the fancy steps, standing on the strewn flower petals, when we should have been collecting maple leaves off the sidewalk. Honestly, we didn’t even need to go so far as collecting the leaves—we just had to notice (a bit more) that they were there.

Let’s admit it! I’m crazy about this passage, to the point of stalker-ish devotion. Why? The piano melody is at its heart just three descending notes (three blind mice), with a hinge in the middle, a node of meaning that comes through the ever-changing possibility of the middle note.

Here the first three notes (B-A-G) are beautiful enough, in the sudden minor.

But just a few measures later, they are replaced by the same three notes in an incredible rewrite, an edit for the ages.

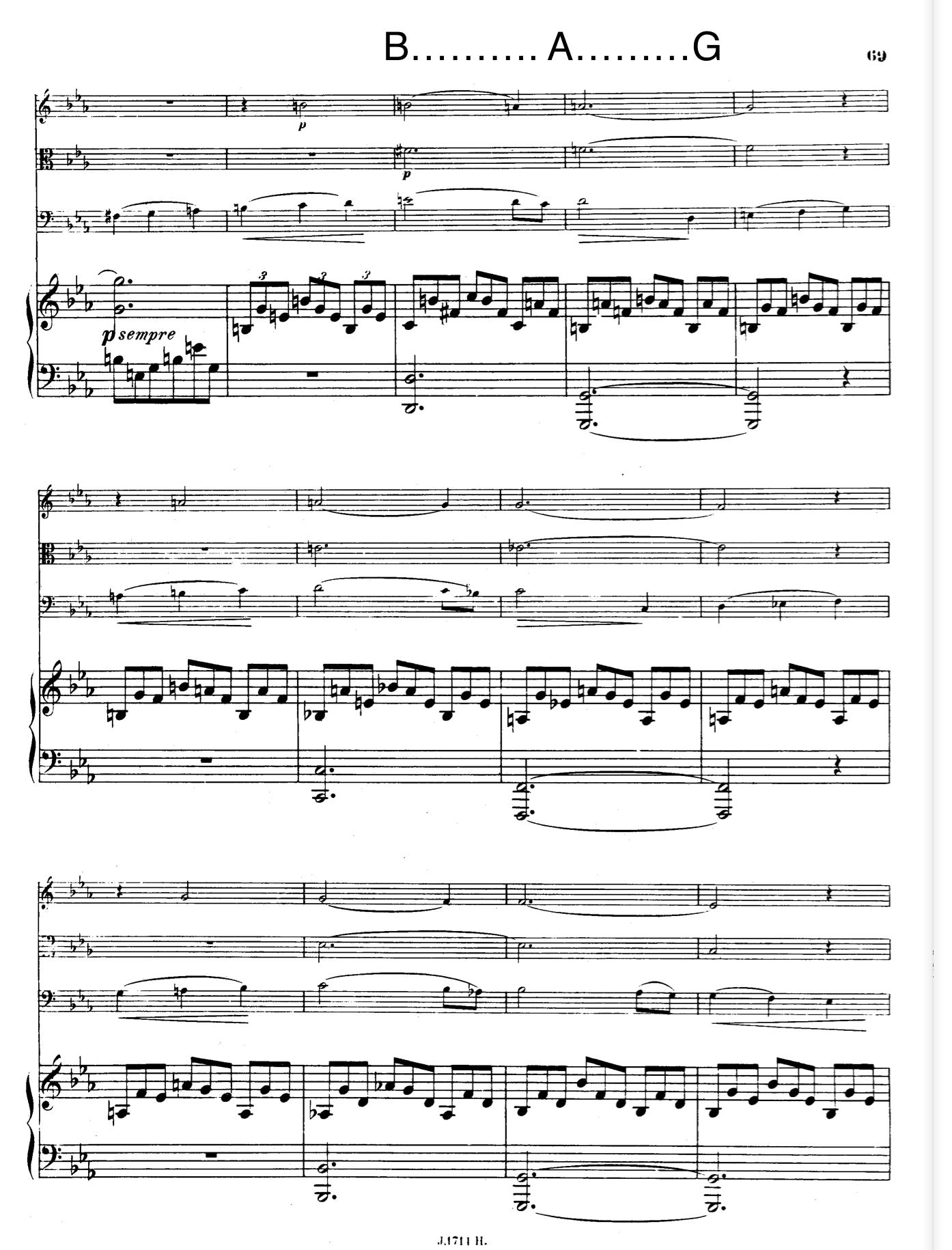

The second version traces upon the beauty of the first, tells a story upon and within it. The gesture, again and again, is dissonance-resolution. But as we go along, the resolutions get more and more sprinkled with dissonances, and the simple binary gets more complicated, in the best possible, most French possible way. There aren’t dissonances or resolutions at last, this mingling suggests. These are not deceptive cadences, as none of these resolutions is, or should be, considered the “real” or “ultimate” resolution. Each resolution just takes you into another world of possible other resolutions, a giant whirl or circle of desire and beauty and pleasure without real end.

I’m sitting there, playing these whirling triplets—you want to freeze frame, stop the action, but still triplets, triplets, triplets, chords, chords, chords. The feeling is incredible, this unfolding of space, an unspooling, as these chords and all the ideas of beauty that they represent come and go. This is a climax, for sure, but not a climax of attainment, built bit by bit through German ingenuity. It is a climax of relinquishing, over and over.

—

This kind of moment, and the unusual space it creates, is one of the great French contributions to the art of music (and art, generally, and life). It calls to mind my favorite Debussy statement—“pleasure is the law.” A paradox—law is usually a constraint on pleasure. Legal writing is prose from which pleasure has been purged in pursuit of unambiguity. But in the magic zone of this music, pleasure and law seem inseparable, the best of friends.

The annoying compositional question is how do you build a musical work packed to the gills with sensual sounds for their own sakes, that still makes sense, that still creates some form of narrative? You can see this fascinating problem operating way back, in the music of Couperin and Rameau (two amazing thinkers), and before.

You might even call this a quintessential French compositional quest: to use more fluid, sensual sounds and chords to sculpt a musical grammar, as an alternative to German logic and methods of construction. So it must have been horrifying for French composers to see this thorny problem cracked by Richard Wagner, of all people. Here he comes, with his orgies of seventh chords and unanalyzable chords, sliding every which way, and yet… somehow … it all goes, it all feels inevitable. A problem that French composers had wrestled with for centuries. I suppose one thing that’s interesting about Wagner’s solution is that while French 19th-century music is often susceptible to (and profits from) different strains of cultural influence (gamelan, Spanish music, Arabic music, etc.), Wagner decided he would anchor his musical adventures in the whitest stories he could possibly find (not just set in white places, which would be natural enough, but coded stories about the glories of the Aryan bloodline) and sell his French-influenced progress as Germanic manifest destiny.

I can’t help posing a modern parallel. The Democratic party, after deeply imperfect decades of agitating for labor power, an increased minimum wage, a more progressive tax structure—they might have felt entitled to some claim to Populism. Hey, we’ve worked at it! These are problems we’ve cared about! But along comes Trump, whose platform has two central parts: 1) hating immigrants and 2) being a dick. He cracked what Democrats had haplessly tried to explain and fix with policy for decades. Being a narcissistic dick was all it took, really, to reach the regular American. Democrats are generally not supposed to be dicks, which puts them in an awkward, priggish, lecturing position.

Narcissism worked equally well for Wagner and Trump, though I would argue Wagner left us astonishing, revelatory beauties and musical ideas to compensate. What Trump’s genius will leave behind, we will now find out in real time.

Great to read your work again (after the book), thank you. We need music, art, and good writing more than ever now and over the next couple of years.

Jeremy, thank you for all you are, and write, and do.

The links to your Fauré performances at Wigmore are marked private. Did you intend this?

I would like to suggest an idea about Substack. I’m an elder feminist queerdo, and can't be a professional violinist any more because disability took that away from me around 2017. (At least I was in my late 50s and had had a wonderful career by then.) I have just enough money to get by: a disability check and a musician's union pension. I have offered to other Substack bloggers the idea of an option for working subscribers to pay a little extra, so that folks in my financial straits might be able to subscribe to premium content. The idea seems equitable and I wanted to share it.

I’m enjoying your book very much. Piano was my first instrument, and you've helped me remember a lot of my "piano origins." Instead of Dohnányi, my teacher gave me the Brahms exercises, which at least bore a resemblance to music. Ceiling Cat bless her for that!

All my kind and buddhisty regards to you, kcd

Northern California