I’ve not been heartbroken in the conventional sense for quite a while, and I’m not altogether happy about it. When a girlfriend broke up with me at Oberlin, not without reason, I wallowed with Mahler for weeks—it was perfect, angsting it up, propping myself on floods of late Romantic whatever, crying on my dorm bed. Every so often I’d take a break, and look out the window with what I hoped was handsome plaintiveness.

It was worse when my first boyfriend left me, not without reason, slicing my concert tux into ribbons, gouging holes in my piano, pouring tequila on the hammers so the whole action had to be rebuilt. The next months were a haze. A precious and beautiful attachment had been lost in a flash—not the slow erosion that aging brings on.

I suppose the most recent version of this for me was the election. The capacity to love the country I live in as an aspiration—that may never come back. The main manifestation for the first few days was fight-or-flight, an inability to slow my nerves. A climax came when I was cooking some dumplings. Some oil spattered. In my state, I retreated crazily, as if fleeing from the scene of a battle, and alas my dishwasher was left open and I fell backwards over it and bonked my head and put a butt imprint in the door. It was hilarious in the darkest possible I-might-have-also-died way.

All the while, I was bringing back a wonderful piece by Missy Mazzoli— Heartbreaker.

For research purposes, and maybe some personal reasons, I wanted someone to remind me what younger love angst was like. I consulted with an undisclosed individual, who’d been left by his love interest. Maybe I was on shaky moral ground. What does it feel like? I asked, if you feel comfortable. He said yes, let’s get down to it, gamely, as if he was just creating a grocery or to-do list, but once he got going there was a glitch in the code. He was looking at himself from the outside and suddenly but what did I do wrong? there must be something! and the person who broke off communications kept changing—was it him or the other person?, the agency kept shifting—and I didn’t have the heart to tell him that this was heartbreak, since he already knew, and yet kept somehow not knowing. It’s over and yet it’s not over.

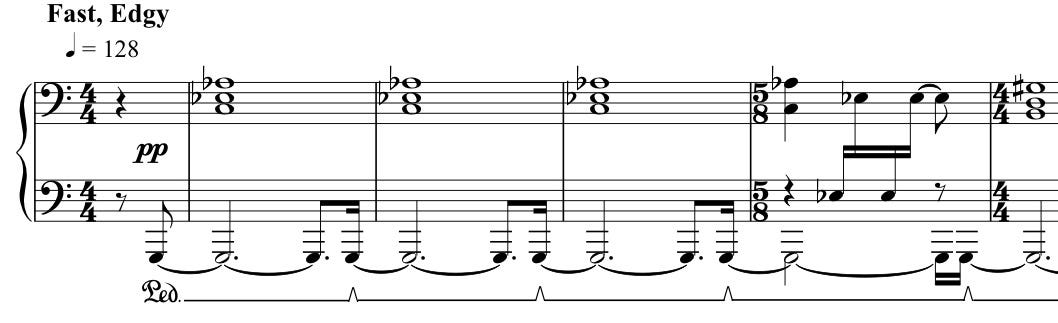

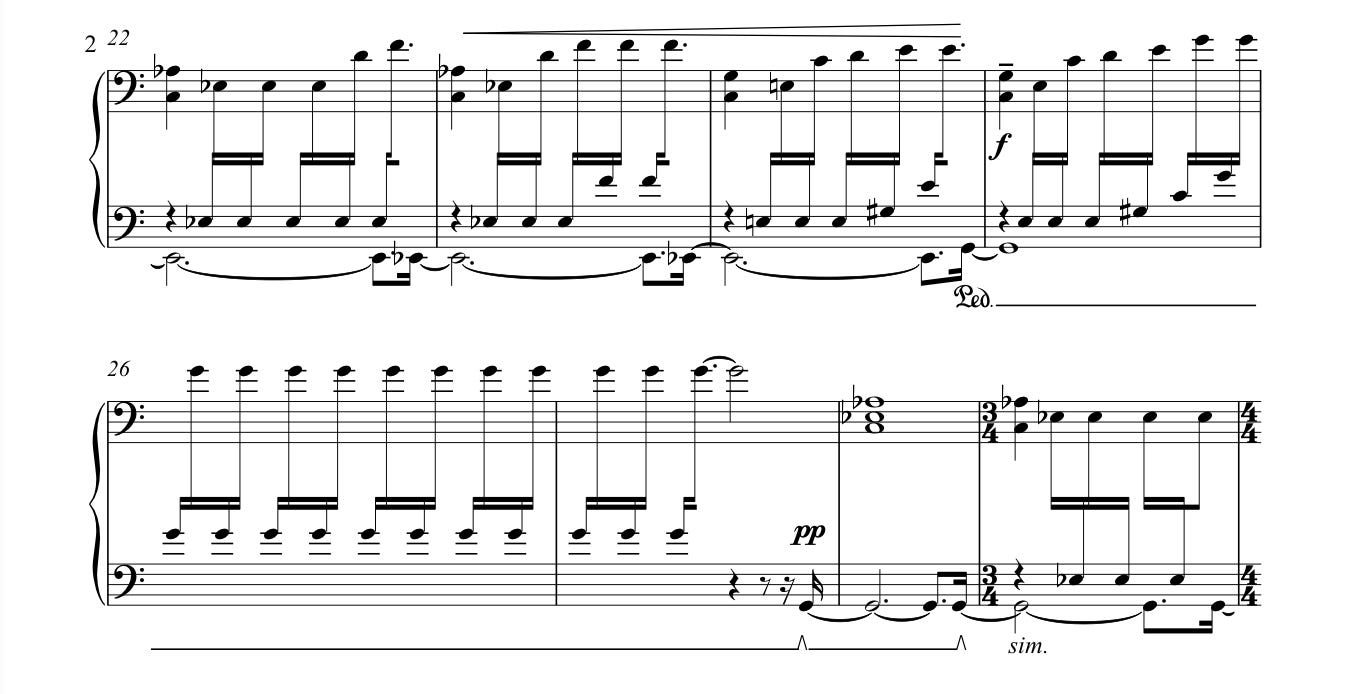

Heartbreaker begins with a series of gnawing dislocations. You could call them syncopations, but that is not, I don’t think, the perfect word:

I can’t help being reminded of the opening of Beethoven’s Opus 31 #1:

In both cases, a dislocation that will not stop, an obsessive split. Beethoven’s after manic, prankish humor. Mazzoli is after … well, I would say… something uneasier. In many post mortems of relationships, you try to identify an intractable mismatch, we are at different places in life, or I’m not sure we have the same values or whatever, some way to make the severing of an emotional contract add up. For the person doing the dumping, often this mismatch is semi-invented to hide a more hurtful truth. For the dumpee, this mismatch may feel frustratingly small, random, almost silly, something that could be fixed or worked on. With the result that the chasm between you is both small and massive, fictional and real.

In musical terms: a major chord in the right hand (A-flat major) and a reiterated dissonance deep down in the left. And what about the rhythm? Music has upbeats—preparatory breaths to the next downbeat. It also has grace notes, which fold into the beat, allowing a grander, deeper gesture. But Mazzoli’s short notes are neither. Too quick for an upbeat, and too slow for grace, they won’t lead in or fold in—they just won’t match up.

In other words, a dissonance in two dimensions: time and pitch. The relationship is flawed, both in substance and occasion.

—

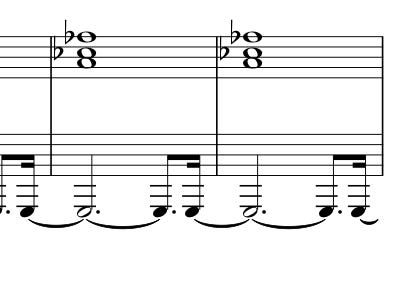

The first narrative event of this piece is that the right hand chord becomes more complicated, beautifully complicated. A-flat travels through this intermediate chord, to C major.

The dissonant G in the left hand stays constant, throughout this transit. By the end, it’s not a dissonance anymore, but it’s not so simple. It remains dislocated in time. And the doubling of the G is odd, now—its own form of instability, just like in certain relationships when you think, oh, if only we spent more time together, but then when you spend time together it hasn’t exactly fixed the problem, and might have made it worse.

Doublings, voicings, resolutions. These are insider musical things, which makes it hard to write about this piece—perhaps that’s why I love it so much. You have to dig into these excellent details as you practice, the haunting by a persistent bass, the coincidence of desired resolutions with a perpetually shifting flaw in the ointment.

—

Mazzoli does a patented Schubert maneuver. She restarts the story from the beginning, then takes a subtly different turn. Here we are at our original chord (plus dissonance):

We still resolve to C. But this time the bass moves to B, just before the C chord:

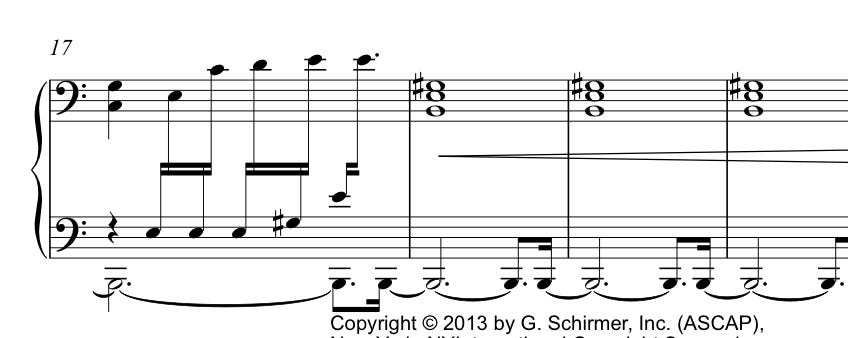

What are the implications? She makes us listen to this rub, this resolution/nonresolution, a couple times. Then, in what I’d call a masterstroke, she brings back the initial A-flat:

… It’s spelled G# now, but you can see it there, in the middle of all those fluttering notes. The color is amazing, if you do it right. You really do sense one chord awakening within another. This old dark note made new (call it A-flat, call it G-sharp) grabs onto the dissonant B in the bass, to find E major.

Is this a modulation? It feels more like a transference, a passage, an elusive path from one beauty to another. The C major chord was beautiful, and this is even more so! A kind of hope. And yet, as we sit on it—its insufficiency is also clear. The fifth is doubled again (unstable, again) and Mazzoli writes a crescendo. Three times in a row she makes us hear it (look up there). Listen! There are forces in this beautiful, hopeful chord that cannot sit still. We are forced to burst back out to more difficult things.

—

Bursting out is key to this piece, played against the feeling of being trapped—both relevant to the world of heartbreak. In my half-asleep 90s, I would yearn for someone, which flooded the zone and engulfed all my other problems. Once you were linked, this became a different flood, almost unbearable, the sense of being deeply and beautifully attached and yet the emotion (which I had not grown up with at all, something my family was allergic to) felt so close to that of being trapped.

It’s statistically likely that Mazzoli has been more emotionally mature than me most if not all of her life, and so this particular problem may not have visited her. But she certainly creates vivid pools of unease. The rhythms are sparse, then burst into flurries, like Tourette’s tics, or Janacek speech-rhythms. The awkward waiting. Then the counting, and sudden action!, repeated notes, a rapid summoning of all your pianistic forces. She varies up the bar lengths in a cunning, screwing-with-your-head way. You must count, though time cannot exactly be counted on.

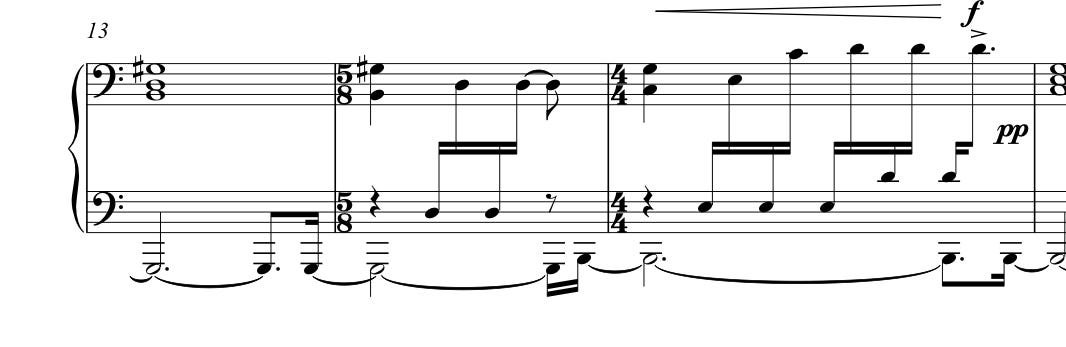

A few flurries in a row, near the beginning, a first big attempt to burst out:

A rhythmic change-up passage comes next, unequal bars, unequal pulses, a heart arrhythmia if you will. Then, it seems, she wants to let us soar:

See the syncopations (a bit of Schumann, maybe) underneath the melody? A sense of flow, breath, continuity, like an old-school Romantic song over a palpitating accompaniment. And yet—none of this quite materializes. The melody doesn’t blossom into a continuous release or catchy hook, it keeps stopping and waiting, and the patterns again are so irregular that a phrase seems like an illusion. Everywhere, could-be or wannabe phrases, bursting and oozing with feeling, sort of resolving, chasing C major like the perfect relationship you never had, and everywhere it doesn’t add up.

At last, there is a terrible build up of desire, in the form of repeated notes for three bars, as if trying to hammer your way out of a cage, and a wild climax. She says, “ecstatic, exuberant” and writes a series of death-defying leaps, full of meaning, unlike my comic collapse on my dishwasher. You’re really just hammering out two notes, over and over, F and G-flat, you’re making many approaches, like an airplane in difficult weather, to a landing in F major. It’s kind of monotonous, this desire, and yet perilously easy to screw up. Like any relationship, it requires tremendous work, and yet it wants to seem easy, thrown off, joyful.

—

I would make a strong case for the canonic value of this piece. I love it, the integrity of it, her uncompromising ending, her subtle harmonic thinking. And yet I have felt heartbroken by it. Until recently, I only felt I did justice to it once, and that was a private performance, on my home turf on my home piano, for my friend Mark Steinberg (from the Brentano Quartet). When I finished, he said urgently, in a semi-whisper, “that’s a great piece,” and that was profoundly gratifying from such a great musician—yes, it is a great great piece but only under ideal conditions.

I have practiced it a LOT. More than most pieces, honestly. And so the frustration is considerable, of not being able to capture the magic, and uncork the genie’s bottle in concert. Recently, though, I started to get closer and closer, to be able to execute all the modern leaps and rhythms and still hear the harmonies in a Schubert-ish, Schumann-esque way.

But curiously all this time I didn’t write Mazzoli. How many times have you wished you could ask the composer (Bach, Beethoven) what they recommended? So, slightly encouraged by recent improvement, I wrote to her asking a simple question, “why is it called Heartbreaker?”

And here was her charming reply:

Hi there!

It was really just a sort of feeling I got from the piece after I wrote it - it’s impetuous, a bit wild, a bit flirtatious and a little out of control. Like a hot guy you meet on vacation. ;)

The piece also had a sense of FUN in it, which is not the norm for me, ha ha, so I wanted a one-word title that was also a bit fun.

Does that make any sense or am I crazy?

Anyway, thank you for playing it!

Missy

First of all, I am glad the composer also wonders if they might be crazy. But secondly, “a hot guy you meet on vacation”… well, that hit me right where I lived! The next time I played it was the best ever—and I started to plan my next vacation. I’d been stuck in a dark loop. It should be a fundamental Rule of Music-Making, at the risk of heresy I’d call it one of the Denk Ten Commandments—you must always remember that a composer’s idea of fun might be different from yours.

One of the truly unforgivable aspects for me about our current moron president is that he and his followers seem to have so much fun, doing their hateful thing. They have managed, even, to make the very idea of fun corrupt, suspect, tainted by the memory of jeering junior high school bullies. Liberals have done their fair share of ruining fun, no question—a major political problem for the left in America. And yet, in the darkness one has to have faith that there is generous and thoughtful and living fun left in the world. That’s why the most severe and deep of the late Beethoven works (131, 110, 106) often have the silliest scherzos: an act of faith. And that’s what saved my heartbroken Heartbreaker.

(credit: drawing by my friend Anya Grundmann)

If generous and thoughtful and living fun is to be found, it's definitely going to be in the arts. Thanks for a terrific essay (and for improving my musical education).

putting the scores in your pieces is so helpful