How to End, according to Bach

with an assist from Shakespeare

I was fired by my therapist before I could explain how many of my so-called adult decisions are schemes to be cool—belated, futile revenge for junior high—but, in a tragic twist, these schemes are all nerdy beyond belief. A short list:

a meta-opera on a musicological tome

a blog punning on my name

Lord of the Rings references in essays on the “Goldberg” Variations

dating a grunge-loving Seattle skateboarder (OK, that one was at least semi-cool and super fun)

Etcetera. Even now, as I find myself writing/playing/thinking my way through the Bach Partitas, this mix of native nerd and desperate-wanna-be-cool reasserts itself. I keep getting up in front of people to explain that a Partita is really a playlist, or—even better—a mixtape.

Some will find this annoying. And yet it’s also an attempt to undo past traumas: lectures on the Baroque Suite from college. Weren’t they awful? I still can feel one early morning in my mind, the chilly windowless lecture room, how he wrote on the chalkboard, and I dutifully mimicked in my notebook…

A C S [opt] G

… which looked like a formula, or a bit of DNA. God forbid you forgot that the Allemande came before the Courante. You’d get docked five points on the exam, or whatever. I don’t remember much of a professorial attempt to animate these dances, to recreate their histories or steps; I don’t remember videos of an Allemande being danced, or anyone explaining that the Sarabande came from Latin America as a wild, lascivious genre and then, on transfer to Europe, acquired somehow—how?—a grave, deep meaning. What a story! Was it a colonial repression of the sensuality of the dance, or was it a slow social realization that sex is a profound aspect of human experience?

Mahan Esfahani, the phenomenal harpsichordist, begins his program note for the Partitas with this dense mouthful:

A project of public self-definition by a composer announcing himself to his peers and to those courageous enough to try their hand at playing the music, the Clavier Übung was from the outset an essentially cosmopolitan endeavour responding to a nascent pan-European sensibility sweeping across Protestant Germany.

I’m not brave enough to begin with a sentence like that. I also don’t have the patience or attention span, since the iPhone. But I like “pan-European,” the sense that a Partita proposes an early European Union. German Allemande, French Courante (or Italian counterpart Corrente), Spanish Sarabanda, Irish/English/Scottish Jig. Or, if you will—and I understand if you won’t—a Partita is a Eurovision contest. Nations get up on stage, one after the other, to offer their best genres, talents, and ideas.

It’s a playlist or mixtape because it presents a such a diverting assortment of tempos, styles, ways of being. An ideal vision of variety. It also has “bonus tracks.” It lies somewhere between a Unified Work of Art and a grab-bag. Some up-tempo, some down, some mid; some lightly thoughtful, others deeply silly. When you get tired of one mode, the next dance offers an antidote.

But the story (almost) always ends with a Jig. We always take our leave by gazing across the English Channel, a gesture you could label—do you feel the pun coming?—Brexit.

—

Who dances an Allemande or a Courante or a Sarabande these days? The Jig is the only dance of the old suite that is still with us. Admittedly, you don’t see people dancing jigs all over the streets, but on YouTube, you’ll find jigging lessons galore. The expression “the jig is up” is still archaically around; also “dance a jig” lingers on in some quarters as an expression of a good mood. Here, already, you see an odd marriage between senses of the word—“jig” as trickery or game or scheme, “jig” as a symbol of joy.

Somewhere I read an account of the Jig’s rhythm, a long-short-long-short-long etc. described as “the natural rhythmic impulse of any dancer who has ever felt happiness.”

In Bach’s Partitas, the Allemandes and Sarabandes tend to be dances of the mind, while the Courantes and Gigues are unabashedly of the body. We need both; the Partita happily supplies both. Bach’s Jigs particularly have a conspicuous, almost crazed kinetic energy. Many of his other dances end with the delicious completion of a chord, a couple anchoring notes followed by tracing of the harmonic innards, whether major or minor or (in this case) both, like coloring between the lines:

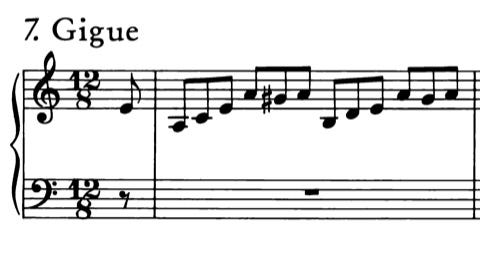

This gesture is an explanation of where we have arrived, a sort of settling in, like settling into a nice cushion on the couch. But a Jig has no patience for explaining or settling. It finishes with an arpeggio or similar acrobatic leap. Therefore these endings are hard to play. The Gigue of the 1st Partita is emblematic

in this case, leaping not just a bit!, but crossing octaves perilously, one hand over another, at last heading for the harpsichord’s stratosphere. The D major Gigue ends with a pair of arpeggios, one questioning its way up (?), leaving energies unresolved, and then a response arpeggiating down:

So, too, the end of the E minor Partita, an arpeggio combined with a curious hopping rhythm (more on that later):

Crossing, hopping, leaps, skips, lunges. Bach compresses essential, almost uncontainable, vectored energy into Gigue themes. He somehow fits it all into a little musical idea, like a spring in a watch.

I find written descriptions of choreography bewildering, but this one (from Wikipedia on the Jig) felt like it held some insight about Bach:

… the rising step, or the rise and grind, is standard in almost all light jigs. The right side version of the rising step is performed by putting weight on the left foot, lifting the right foot off the ground then hopping on the left foot once. Hop on the left foot again, bringing the right foot back behind the left foot and then shift the weight onto the right foot, leaving the left foot in the air. Dancers use the phrase “hop, hop back” for these three movements, and there is a slight pause between the hop, and hop back. The next movement is a hop on the right foot. Then shift the weight, left-right-left-right. The phrase for this whole movement is: “hop, hop back, hop back 2-3.” To do the step on the left foot, reverse the left and right directions.

Any paragraph about “rise and grind” would appeal to a coffee fanatic like myself. Now (with that description fresh in your mind) turn to the theme of the D major Partita’s Gigue:

One of the most delightful and infectious of his inspirations. The first gesture arpeggiates up, then radiates back down, and then back up, and stops. It feels asymmetrical in a way, an open-ended gesture, and yet there is palindromic symmetry in it too: up/down/up. The silence at the end of the second measure is essential (“leaving the left foot in the air”).

Then a new idea, hopping down from B to E

and after a little pause again the same, hopping one step lower

Perching for a moment before the next release, playing on the wonderful tension between moments of poise and the dance’s desire to rush and bound onwards.

Look back at the Wikipedia jig, the “hop, hop back”. Two hops—perhaps the beginning of a pattern? But no, now we get a gesture that refers back to the first in reverse

more roving arpeggios, this time down/up/down, and an epilogue scale which leads us back into the theme—a relay rod being passed from one voice to another. And so it continues, to the second voice, and on and on, with the implication of infinite regeneration. Later, these epilogue scales will play an amazing game of ping-pong with each other, passing over, sliding under, running, while a third voice tries to contain this energy within harmonic understanding. I think you don’t really play these dances so much as surf them.

—

One of the key, non-negotiable virtues of Bach’s Gigue themes is unpredictability, a leaping or swerving that comes from nowhere or out of nowhere. The theme of the A minor Gigue is a classic example, where Bach sets up a pattern in the first measure:

This has its humor—a leaping arpeggio keeps getting waylaid by a stubborn chromatic wiggle on beats two and four. But then, the third time around, the leaping arpeggio is followed by a feint, or a dodge, a syncopated swerve around a B-flat:

Oh yes, that is fabulous, both the change itself, and more than the change the sense (even within a theme that will recur again and again) that at any time, a chromatic curveball might take us off the familiar traffic circle of fugue onto a road we’ve never seen.

In the D major Gigue, it is almost impossible to know what form of groove comes next. Take it from me, having played it for 25 years or so—I still find myself surprised when the left hand suddenly interrupts, or that an A# appears to bend us into B minor, or whatever. There’s a moment in the first half of the Gigue, where it seems from the chords on two and three that we’ve settled into a nice rollicking oom-pah-pah:

But, just as you begin to feel grounded by the rhythm section, Bach removes it, and lets fast flowing notes free to fly all over the keyboard:

Unmoored rhythm, looping at will. I particularly admire the little disruptive “wrong” accent on the second sixteenth there, the B, the bump in the road, a little accident to play with you or (joyfully) confuse you … and after that of course Bach (never mean-spirited) gives you the most wonderful grounded cadence you could imagine.

—

It is curious, verging on perverse, that Bach’s jigs are fugues. It’s something I’ve taken for granted for so long that I forget to think freshly about it, to re-absorb it. Jigs are the ultimate fun dance and fugues are (to say the least) not everyone’s idea of fun.

Now (putting on, with a sigh, my music history hat for a moment), this is part of a long tradition—back to Froberger suites, a great North German keyboard forebear. Are any of you also having stomach pains, recalling on Froberger from college, having to memorize “Stylus Phantasticus” knowing that you will forget it again for the next twenty years? Poor Froberger! Not the sexiest composer name. Not many people are throwing Froberger projects or festivals these days. He is the undeserving victim of untold jejune burger jokes (including this sentence). Credited with inventing the suite as we know it, he is also a delightful door back to Italy, to Frescobaldi—and maybe part of what we love about Bach is, as Lutheran and German as he is, a little Italian wildness flows through his musical veins.

Have a moment’s pity for Froberger! Watch this video of the harpischordist Marco Mendoboni play him with love and great musicianship…

I adore everything about this video, not just the playing (the Allemande so free and operatic, the Courante so full of two-against-three dance energy, etc. etc.) but also the Stevie-Wonder-ish head shaking, the tuxedo despite the empty room, the bowtie barely tied, on the edge of chaos.

Yes, so the fugue-gigue dates back to Froberger. But still—these two genres are an odd, incompatible couple. No question, a mashup, and (also no question) Bach found tremendous inspiration and pleasure and creative interest in forcing them together. The rollicking energy of the jig absorbing the propagating energy of the fugue, or vice versa. Which one will win out? Is the jig the cool and the fugue the nerd…?

—

I was lost in the labyrinth of what a jig might mean (as it happens) on a New Jersey transit train, a late transfer from the corporate subsidiary of hell known as Newark Airport. The travel gods had karmically smiled. I’d hopped on an immediately available car to find myself in bright fluorescent light, surrounded by heaps of people in weird silence, careening east in hope or sorrow or the deadened rut of a commute. I was asking myself again and again, why do these pieces all end with jigs? I was Googling jig links as fast as I could, and there it was: a person who jigged from London to Norwich, also eastish, about 80 miles.

Will Kemp—famous clown/improv-comic—was fired from Shakespeare’s theatre company, possibly because his end of show antics (known as jigs, or jiggs, or giggs) were getting out of control, or his improvs were too bawdy or distracting, or who knows? As a form of protest, he embarked on a massive publicity stunt, eerily as if he understood social media already, in 1597. He had a drummer follow him, and a documentarian, and he danced his way to the coast of England in nine days, spread out over a few weeks.

The theatrical jig! This hadn’t been part of my musical/cultural understanding or my liberal arts education. What the hell? I wanted to call my Oberlin English professor and lodge a complaint. If only I’d picked up a copy of Grove’s dictionary, where the musical and theatrical jigs have definitions right next to each other…

But no, I hadn’t, not for years. So now, sitting and passing under the Hudson River tunnel, a vast network of connections and meanings seemed to spread out. At the end of Shakespeare’s plays, jig epilogues were mini-scripts, often bawdy, full of word-play. Dancing, rhymes, trickery, a bit of filth. They are referred to (somewhat disparagingly) in Hamlet. There was tension between these popular comics and the authors of the dramas. The comics would insert their improvisations all through the “serious” play, upstaging it. So they were placed at the end, as dessert, given their moment only after the audience was forced to sit through the main event.

Yes, maybe Shakespeare and his well-loved comic actor Will Kemp fell out over this. And yet where would Shakespeare (and we all) be if not for the fools and jesters and comics (obviously inspired by Kemp and his ilk and their gifts for relentless, rollicking word play)? Where would we be without Lear’s fool breaking our heart while he sort of jokes (in the lilting cadence of a jig, it does seem important to point out)

The codpiece that will house Before the head has any, The head and he shall louse; So beggars marry many. The man that makes his toe What he his heart should make, Shall of a corn cry woe, And turn his sleep to wake

… or bitter Thersites in Troilus and Cressida, making relentless fun of brutish Ajax:

Why, he stalks up and down like a peacock— a stride and a stand; ruminates like an hostess that hath no arithmetic but her brain to set down her reckoning; bites his lip with a politic regard, as who should say “There were wit in this head an ’twould out”—and so there is, but it lies as coldly in him as fire in a flint, which will not show without knocking.

Or Bottom in Midsummer Night’s Dream? I felt a connection from these endless word games and images and tricks—tricks that take on tremendous importance, that stand in proximity and play witness to the deepest tragedies and shades of human feeling—to Bach’s way of playing games and tricks within his gigues, and to the whole gesture of ending these grand pieces with them.

—

There is nothing more disappointing than a bad (or pompous) ending. One of the most vicious disappointments in recent years was—need I even say it?—the crash and burn of Game of Thrones—an almost moral example, the tragic flaw of it, the swift and total collapse of narrative competence. I thought it was absolutely hilarious that they decided to follow the grand last battle with an awkward, extended board meeting. And who knew? a show that was almost entirely about massacring people would end with yet another, bigger (yet somehow more anonymous) massacre.

This sense of a predictable ending rumbling into view is so sad. The novelty and unknown of the premise congeals. Oh yes, now we will have the Final Showdown with the Bad Guy, or the guy will run to the airport to declare his love at the gate …

But Bach’s Partitas do not have that problem. They swerve around the problem of ending, crossing between genres, offering extravagant and deep wit. The mad pile-up of trills in the second half of the G major Gigue, or the sudden “wrong notes” twisting into minor in the B-flat, or the fact that the Capriccio is not a Gigue but shares the wild intervals and syncopation, or the last one in E minor, starting like a sober academic fugue, but halfway down the page, visited by a hopping in the left hand, an irrepressible Gigue-ness dragging us into another realm. I’ve spent so much of my life wondering how to play that one. There’s something beyond the pale about it, an emotional ambiguity and a relentlessness (like Shakespeare’s fools.)

They prove beyond any shadow of a doubt, that you should not play fugues woodenly, or—like certain teachers seem to prefer for Bach—as if every note is engraved on a granite tablet. The instruction for fugues that I get from these gigues is: dance your ass off. I tried to think of a more polite, musicologically sound way to express this, but I couldn’t.

Bach ends his Partitas not by arriving or settling, but by leaping, and there are so many types of leaps—of mind, heart, imagination, faith. As we jump from note to note and rhythm to rhythm the result (I’d argue) is a kind of catalogue—here, he says, are many wild ways to be happy. In Biblical terms: Go forth and multiply! Or, to put it in terms any TV-weaned American like me can understand: just be cool.

Which musicological tome was it that inspired the opera?

"Forbear" should be "forebear."