How to Begin, According to Bach

a lovely lesson

If you’ve ever ended up in the bed of an opera singer (it’s been known to happen) you might wake to the opposite of a mating call: the sound of warming up. Vocal warmups are an antidote, and a cold shower. All the glamor of opera erodes, the tossed bouquets wilt, the screaming standing ovations fade away. In place of the great history of the glorious medium what you hear is just five phlegmy notes up and down, or a frog-like yawning through intervals, a wobbly seesaw which sounds, especially to the hungover listener, like an acid reflux of the soul.

Maybe it’s at this moment you feel most profoundly the connection between muscles and frequencies. Squats—through notes. I’m not going to claim my keyboard warmups are fun to hear. But the muscles I am testing and stretching are hidden away, while you feel the singer’s notes and flexing muscles are present, and somehow the same—the chords are cords. Lying in bed, your ears face the singer’s musical anatomy head on, the bodily nature of music, before you’ve had any coffee whatsoever.

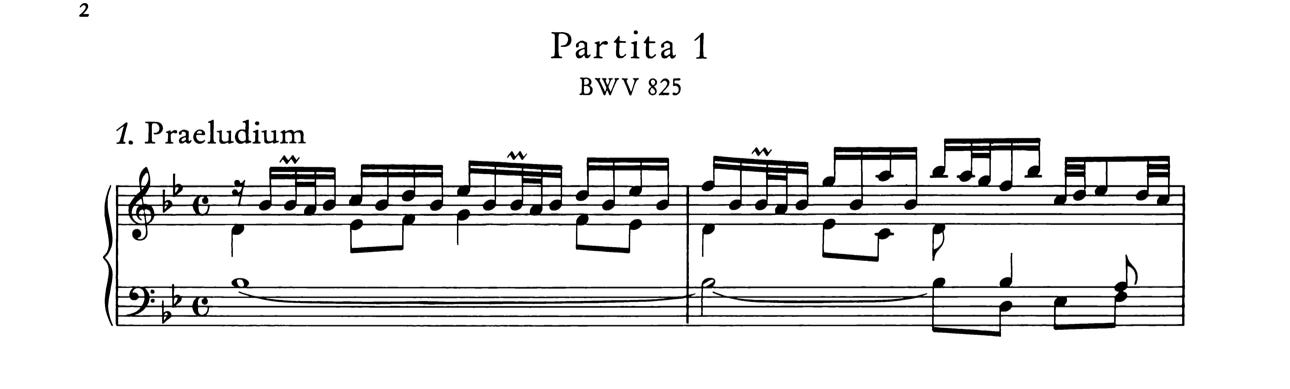

I think it is rather extraordinary that Bach begins his first Partita (his first published work) with measures of warming up. You’re not going to catch Beethoven doing something like that. Maybe, for instance, at the beginning of the “Tempest” Sonata you might imagine, oh, I’m going to play a sly, slow arpeggio to get myself used to being awake

But then—much like my father on Saturday mornings—Beethoven tells you to get your lazy butt out of bed

Beethoven’s not generally a big fan of easing you into his pieces. He wants to unsettle or grab or terrify you. Even in his soft, tender beginnings, for instance the opening of the 4th Concerto or the “Archduke” trio, it’s not like you get time to wake yourself up. You must suddenly and instantly play with ultimate sublimity, as if you fell out of bed right onto the top of Mount Olympus.

But here, you have a nice middle of the keyboard B-flat major chord and a little trill. A piano teacher at Oberlin once told me that trills were one of the best ways to start warming up in the morning, far better than scales, which made unfortunate demands on some small muscles. It was better, he said, to ease into all that. I ignored this suggestion for years, a policy I follow with all excellent advice. But here it is, from Bach himself: start with a trill, only then move on.

—

There is an unarguable delight to these opening measures, and I suppose one motivation for writing is to somehow account for it. I am so tired of reading about Bach’s genius, to be honest—I have contributed epically to this problem, with oodles of What Makes Bach Great content. I guess what I’m proposing here is that what makes this movement so alluring is the greatness of non-greatness.

If you’re seeking universe-altering stuff, you might look to the Sarabande of the 6th Partita:

Mad whorls and complications. A dance buried beneath a frenzy of ornaments and yet somehow also the sighing, the sorrow, the spine of the dotted rhythm, keep fighting through all of it, reasserting themselves. This Sarabande holds so much of Bach’s understanding about prolongation, deception, elusive chromatic wandering. You find layered wisdom and depth, clouding the possibility of a final understanding.

But here

the music is as transparent as a window. There is nothing to understand, as there is nothing to puzzle over.

One thing I adore about this nugget of music is how (after the trill) it rises a bit up the scale, and then (after another trill) a bit more, just one step more. Inching up the scale, like an inchworm. And then, the third time!, suddenly Bach sweeps us to the top of the scale, to the high note, a B-flat, as it happens where we also began.

As often in Bach, a metaphor hides in the musical idea. You take one methodical step; based on the first, you take another. They seem like humble steps, which might not get you anywhere, but somehow incremental steps forward lead us—who knew?—far above and beyond. 1+1 equals 5. This is true of piano practicing, and many other endeavors, and as such you could say this theme describes a little act of faith.

The other main thing I admire is Bach’s little dance around the high B-flat, once we’ve arrived. I am not a marvelous dancer, as my ex-boyfriends (and -girlfriends) will attest, but not so long ago I invented a dance for household use. Whenever I manage a minor domestic achievement, for instance clearing smelly takeout remainders from the kitchen counters, or showering two days in a row—I perform the “nicely done dance.” It is funky, at least in my mind. There’s a lot of wavy manic arm motion. The footwork is free form, verging on anarchy—some hopping, some skittering. It lasts less than ten seconds, and sometimes results in injury, but still, it’s so pleasing! My partner enjoys the nicely done dance, but never joins in. He feels I over-celebrate my accomplishments around the house.

In this case, Bach is letting us celebrate the modest accomplishment of a B-flat major scale. We fall a bit away from the peak B-flat, then—in a syncopated piece of fancy footwork—return to it, then scoop way down, with more little syncopations, to where we started.

If you feel I’m micro-analyzing this bit of music, consider that Bach did make it the first musical utterance of his first published work. Everything in this prelude is woven from it. There are no contrasting materials, no episodes to speak of, no subplot. Only this idea, and the simple joys it represents.

—

As we make our way through this musical invention, we visit all of the intervals, like a singer might—seconds, thirds, fourths, fifths, sixths, sevenths. We are opening up a space, or stretching a muscle, prudently, step by step. And we keep returning to the main note for grounding, to touch base, as if the low B-flat was a spotter at the gym, helping us forward with stability. What’s next? Also like an exercise routine--we switch to the other hand, so both lobes of body and brain get a good workout.

There can be no question, this is music of the morning (while the 6th Partita, for instance, belongs in deepest darkest night). It has an optimism. I have this thing I do with students, drawn from my Juilliard doctoral dissertation. Sometimes I get tired of asking them to define character. Yes, it can be helpful to know whether they consider a passage of music to be “playful” or “triumphant” or “flirty” or whatever it might be. But, if I’m really ambitious, I ask them to define what they think a musical passage does. If you had to pick one verb, what would it be? Sometimes I invoke the famous scene from Silence of the Lambs where Hannibal Lecter instructs Clarice to ask what does the murderer want, what are they doing? It’s not always easy to pin down a single verb for a complex musical passage, and yes it can be reductive. But here it does seem reasonably clear. This beginning wants to rise, like a dough or an aspiration or a person in bed listening to a singer warm up.

The morning is the time of day, at least for me, where it seems most possible to get things done, in the first flush of coffee. The afternoon might be a decent time for editing, but the morning seems best for imagining, reaching.

The left hand does its thing—rising—and in our third visit on this same material we slide into the minor. Isn’t there always some bit of melancholy in the morning, even while you’re still rising? (Oh God, another day, but here we go.) The lovely melancholy doesn’t last long, we escape from the minor with this leap to the high B-flat (rising, the defining urge).

In the final bars, you can feel Bach revealing an ending to his open-ended verb. The curtains begin to close on the scene. The right hand descends while the left hand ascends

… a powerful wedge motion, a focusing of the musical intent. In the last bars Bach begins to add more notes, many accidentals, to thicken the chords, to give them more heft. Maybe at the beginning we were playing on a modest demure clavichord, but now the instrument seems like it wants to be an organ. Or, another metaphor: we were just making coffee in the kitchen at first, doing tasks, emptying the dishwasher or saying prayers, journaling, stretching—who knows what sort of simple incremental tasks we all use to get going each day, with the faith that they will help to bigger things?

But now, in the final measures, there’s unmistakable grandeur—

It doesn’t matter how simple or small the material was. No, Bach says: the smallest things can be grand, should be grand— in meaning and in reach. It took very little for Bach to tell us this story, honestly. Look back at the page! It’s easy enough to see what he’s done, and how he’s done it. A bit of this in one key, a bit of that in another, over and over. The sermon is not that this kind of greatness is inaccessible. No—there it is, easy peasy, step by step. You, too, can be grand (and you are). As deep and incredible as the other Partitas are, I’m not sure if this way of beginning isn’t deeper, or more important.

Brilliant, but please tell me there’s video of the “nicely done dance.”

this is like the way I write about pieces I enjoy, too, and it makes me feel giddy to read another's rambles that I feel in my soul (though I haven't listened seriously to this particular piece yet. Time to fix that!)