In Toronto, I was listening to a gifted young pianist play Haydn’s Variations in F minor. It seemed like the perfect escape from politics and an overriding pessimism: to throw myself into art, and the act of giving to the next generation of musicians. But as soon as he started—strange to say—I was jealous. Not to run up to the stage and take over. My craving was even worse. I wanted to crawl into bed and wrap myself in the gorgeous sadness of this music like a blanket, with bags and bags of unhealthy snacks, and stay there for four years or more, depending.

Sitting in the audience, trying to look like a serious teacher, I wondered—what is it about this particular musical melancholy? Why does it ring so true, feel so real? We are bombarded by fake sadness these days, so much aggrieved whining and childish, feigned outrage dominating the news cycle, trickling down into our lives. It felt amazing to drink pure, adult unhappiness. It made me want to unpack it, to see what consolations or truths were held within.

—

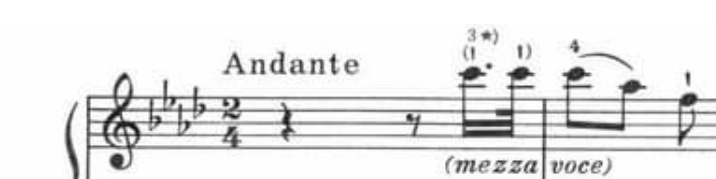

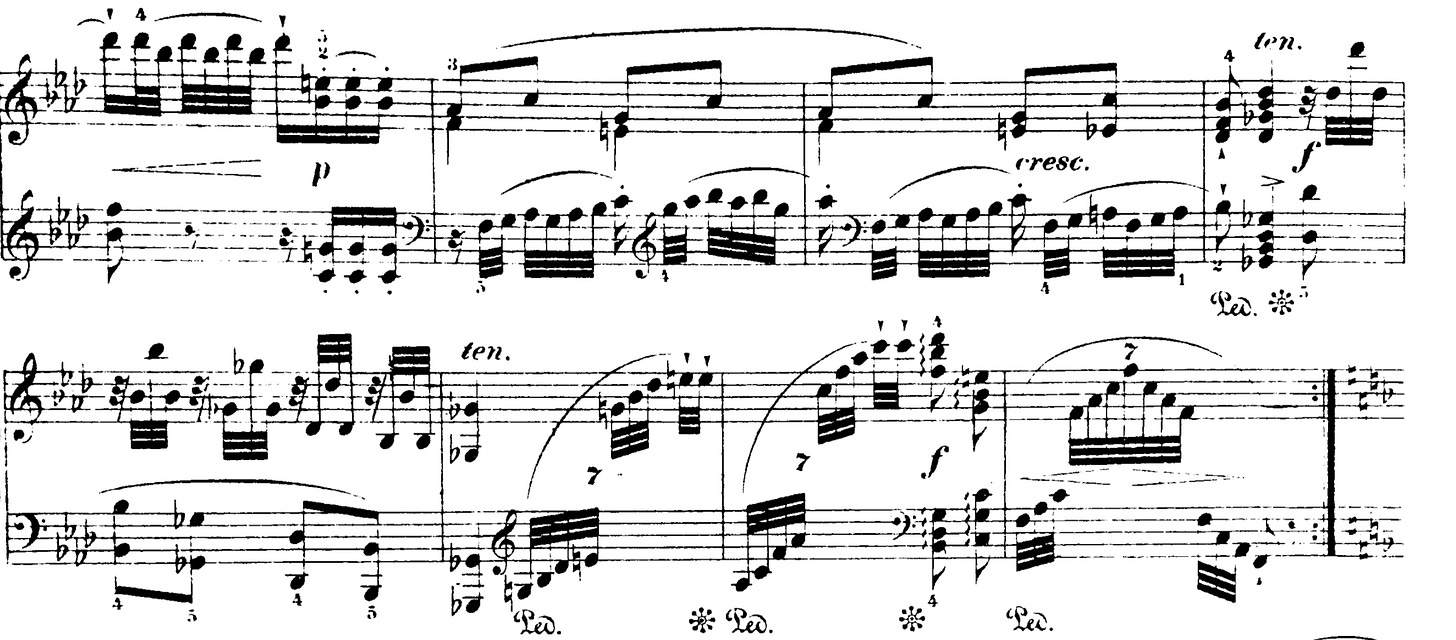

The first thing to admire is the empty bar we start with:

It’s not empty, exactly. We have the presence of an accompaniment, a sense of pace, a rhythm—but it communicates an absence.

In this not-empty empty bar, I gave my gifted young pianist some grief for neglecting the slurs. Andras Schiff agrees with me (as you may see in this video). It is essential to play the little slurs, nested within the big slur. If the second note of each beat is released it creates a little sigh within the pulse—this is how annoying details become eloquent.

For Schiff this detail primarily helps to create the feeling of a funeral march, a processional. I’m going to risk semi-disagreeing with him. First, my bias: I’m not a massive fan of funeral marches. I prefer the soaring middle section of the “Eroica” slow movement to the trudging main theme. I’m not wowed by Beethoven’s or Wagner’s funerals for heroes. I dread that famous Chopin one, with all its repeats, and absolutely adore the unrepeated, unrepeatable, nihilistic wind over the graveyard that comes after.

A funeral march suggests some pomp, a sense of public occasion. Does this Haydn theme feel like it has a sense of occasion? It seems oddly fluid for a march. The texture is lighter than you’d expect, more treble-focused. Its rocking motion almost feels like a lullaby at times (at other times, definitely not). Yes, a funeral march is one of the musical referents, but what’s so compelling and amazing about this theme (it seems to me) is that it lives on the border of other genres: a lilting folk song, a lament, even a slow dance, at times an improvisation.

In this way, Haydn reduces the funeral march down to size, making it more private, more personal. Music history is littered with commonplace pieces for grand sorrows—deaths of dukes and kings and patrons, bloody battle memorials, etcetera. But here we have the opposite: a grand piece for common sorrow.

Schiff makes a big deal of speculating that this piece might have been about the death of Mozart. This rubbed me the wrong way. Aside from a total lack of evidence, is it only true sorrow if it’s about a musical celebrity? Is that the only way we can appreciate the depth of it?

—

In my spells of sadness and depression—after my parents died, or my friend Michael, or when I was worn down by other stresses—I learned one thing. Once you begin to feel you have control over the darkness, you don’t. It morphs under the surface and bites you in the ass, in some other amazing and unforgettable way. Sadness has an unsymmetrical, unpredictable shape; it narrows and then explodes.

This theme, too, is asymmetrical and unpredictable. It could never go in a handbook for How to Write a Melody—it is too much of a one-off. It has three peculiar parts.

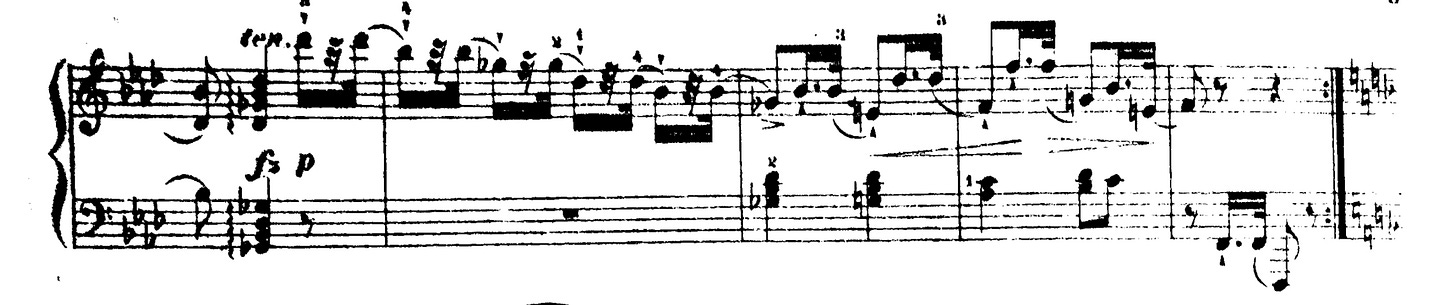

The first event is a falling gesture (a fifth):

Beginning with the dotted rhythm. Calling it out, as if naming the melancholy, or just giving vent, then releasing.

The second event is more bizarre—more Haydn. The melody, before it can even really get started, gets stuck on F:

This presents an interpretative problem—how do you give direction to the directionless? Pianists especially struggle with shaping repeated notes. It is such a choice, this pokey morass, with a meaning that comes from awkwardness and limitation. But anyone who has been through a depressive episode knows what it feels like to be stuck on one note.

The third event: Haydn marks “tenute,” the melody becomes legato—and we are no longer confined. We find ourselves in a frenzy of scalar motion (you might say, an outpouring.)

These scales are of course not just scales; they make you feel most of the possible “blue notes” in the F minor world. We retrace the opening gesture, touching every painful note in between, and then we feel out the fifth below, as if exploring consequences. In the second measure, we glance by a couple naturals (E-natural, D-natural, a glimmer of light), then contradict them—painting over tenuous light with darker hues. In the third bar a stubborn remembrance of A-flat makes resolution wait. This could have been a two-bar finish, but Haydn manipulates it to be three, to give it extra complication.

This last part of the theme couldn’t be more different than the previous part. And yet in both—stuck on the F, wading through lingering suspensions—the music evokes the idea of refusing to let go. An essential trait of sorrow, seen two ways.

—

Schiff starts his class by being annoyed with the student for playing an extra five measures that he hadn’t known about. This annoyance bubbles up again later, when he criticizes the kid about his breezy approach to the major-key variations.

“Is this a tragic or comic piece?”, he asks, in a super-vexatious Hungarian tone.

I stared at my iPad screen, thinking—tyrannies hide in binaries. The poor student has to say tragic, because the other option is ridiculous. I thought it was unfortunate that Schiff would pose this false binary in this particular piece, a piece all about the incredible complexity and nuance possible within pairs. It’s honestly a miracle that Haydn can write a piece with two themes, each in binary form, inhabiting Western music’s pair of major/minor—a maze of baked-in dichotomies—and still make it feel so fluid, so free, so philosophically interesting.

Schiff knows there are millions of degrees of lightness before you arrive at “comic.” You can be hopeful, or blissful, or suddenly lifted, or even light-hearted, or manic—all different from comic in important ways, and all of which fall under the sway of the major key.

“Tragic” has issues, too. The piece ends with an extraordinary swerve to the dark side, and yet the word “tragic” buries the other half of the piece (and its contradictory lightness) under the weight of a label. Tragedy also tends to suggest noble things, noble people, and fatal flaws. I don’t sense any flaw. There certainly is no hubris. An unfortunate event has already happened, or continues to happen. What’s left to contemplate in the piece’s weird two-faced way is just life, time, death, illness, loss, or change itself.

—

As I listened on to the young pianist play, in between moments of surrendering to the music, I kept murmuring to myself—against my better judgement—the phrase “both sides.” An endemic epidemic phrase nowadays. For instance “now that the media’s tyranny has been lifted, you can hear both sides” or “universities should teach both sides” or crap like that. In junior high school, in 1982, our teacher made us have a both-sides discussion of creationism vs. evolution, and even back then I wondered what the hell we were doing. What is the line between a productive debate and an irresolvable culture war?

From the moment “both sides” is uttered, you are likely not in a meaningful discussion. The game is already rigged. Issues of import to our lives do not (and should not) have two sides. They have many sides, shades, perspectives, so many! But how then do we deal with a world which prefers to paint in twos?

Haydn’s F minor variations are—in a sense—an obvious essay in “both sides.” The heartbreaking minor key theme ends:

And then after a silence (a lot of nuance in how you play those silences!) comes a new major-key theme, not so heartbroken:

Almost the first thing Haydn does is to reinterpret the A-flat of the minor, to show that that single note has “another side.” (In the left hand, that G-sharp…) Why is the first measure of the new theme a chromatic measure? This is a real choice, a real Haydn maneuver, to subtly draw connections between the two worlds.

How can we interpret these connections? So many ways. In the minor-key world, the A-flat often exists to resolve down. In the major-key world, the G# (the same note) moves up. From this fundamental bit of music theory, we can extrapolate a bunch of easy dualities:

Down/Up

Pessimism/Optimism

Despair/Hope

You can come up with more dichotomies till the cows come home.

But what Haydn is painting is far richer than that. Consider that A-flat serves as a kind of icon of the minor: a column within the minor chord and all its melancholy. But in the major, the G-sharp (the same note) often appears as a kind of ornament within a more rococo, pastoral, charming style.

This transposition from one style and expectation to another is not just a change of outfit, or a clever pun; it is subversive. How can sadness exist so deeply within a note, and then it becomes just a passing note? How, indeed, can someone be afflicted by tragedy, and others pass by as if nothing has happened, living frivolously? (Auden on Brueghel, the obvious reference here, but there are so many). Forgive a deliberately shocking analogy: you take someone’s heartfelt poem about the loss of their child and you make it into frilly curtains for your living room.

This sounds ridiculous, maybe. But this aspect of the piece is real, all too real, and far more truthful than most elegies or eulogies—the moral that at any time when someone is suffering, someone else is laughing it off, loving it, not caring. And the suffering and the obliviousness are often woven from the same materials. On a grand national scale this is playing out as we speak. Some of us think of America shifting towards the truth-free oligarchy of modern-day Russia, while countless others see Peace, Prosperity, a new no-nonsense American paradise.

—

I kept watching Schiff. He seems to want to bring the two variations under one basic heading. Let’s concede that sometimes his gifted young pianist plays the major key variations too flippantly, with not enough love, not enough care or cantabile.

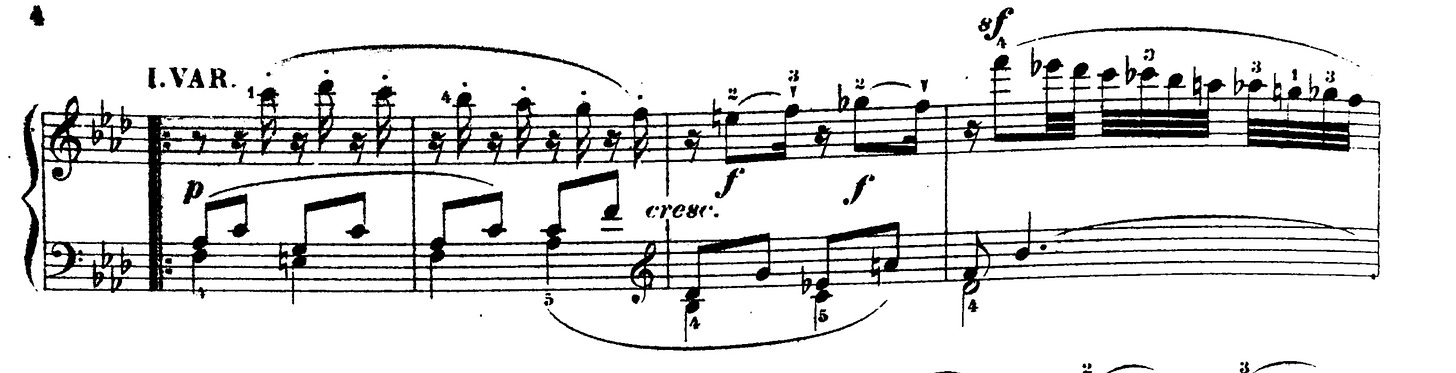

And yet! I wonder if there’s a more radical perspective to bring to bear. After the first major-key theme, the minor returns, and exaggerates its own darkness, with more chromatic notes, and extreme sighing:

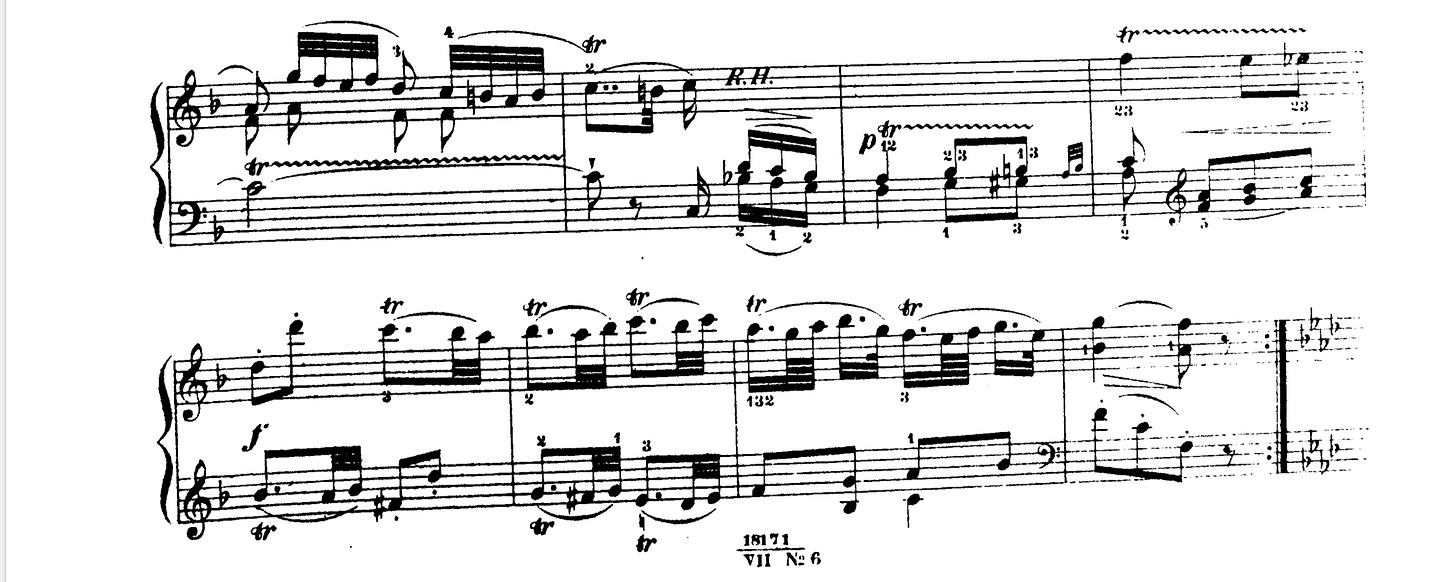

Seemingly unperturbed by this, the major returns and adds a bunch of trills, exaggerating its own ornamental aspects. At times it seems almost absurd, the amount of froth Haydn crams into the texture:

A phrase to describe this procedure, borrowing from modern political life, is “double down.” The ensuing minor variation similarly doubles down on darkness, and verges towards fury:

After all that, inexplicably, the major responds by doubling down again (!) on ornament and frill, an orgy of lightness:

This is not just odd; it’s an enormous interpretative issue to be reckoned with.

Schiff seems to be after a single-voiced, noble memorial piece, of great dignity and expression. I think it’s just as possible to hear two voices, in two sets of variations, heading off in opposite directions, in a kind of red-blue madness, an emotional polarization. I’d also argue that Haydn doesn’t create a “sensible middle.” He’s not seduced by the idea of some golden Goldilocks compromise between major and minor, the kind of thing proposed by chin-stroking common sense centrists, like the well-intentioned David Frenches and David Brookses constantly trying to tell us where the American sweet spot is, what is reasonable, etcetera.

The piece ends (spoiler alert) with a giant, catastrophic explosion of the minor, and then, at the last moment, by definition too late, a tiny eerie vision of the major, as the piano cries out into the treble.

There is nothing reasonable about it, even though the piece comes out of the heart of the Enlightenment. A middle ground is nowhere to be seen. Haydn wants to show us that the opposites are intertwined. But he does not reconcile them.

—

I thought about the pastoral a lot while listening to my gifted young pianist (and Schiff). This is how I understand some of the major-key sections, with their crazy trills and ornaments. These passages seem drawn from this classical world of shepherds, curvy nymphs, fluttering breezes, an alluring paradise of nature reborn, a lost paradise obviously.

In the world of the pastoral, of course, no matter how delightful the breezes are, coming off the Aegean Sea or wherever, no matter how contented the sheep are, grazing on the rocky hills, there is always the other side, where the same force becomes deadly. The happy fertile rain of spring, helping to bring forth nature’s bounty, becomes the killing frost of winter. Seasons are a form of regime change. Both sides!

I wished my student, as he played, would have more of this uncertainty, this helpless awe in front of the shifting faces of nature or fate—or however you want to put it. I felt similarly about Schiff, to be honest. Control seemed central to his vision of these variations—but the piece, viewed another way, is more about how certain variations are beyond our control.

In the pastoral, the main character is change—all the others are bit players. Everything is a matter of living in the now, while being prudent enough to survive some (but not all) changes. I wonder how those classical shepherds and nymphs would feel if they knew that humanity was aware of a force that would change the whole nurturing system of seasons, irrevocably disrupt the cycles, and leave everyone even more prey to catastrophic uncertainty, and yet, even so, they would chant “drill baby drill”, as if wanting to burn down the whole world out of spite. Even those shepherds, so intimately familiar with the selfish whims of the Gods, might have found this a bit too much to believe.

I love this piece almost as much as I love Haydn. For me, Schiff has always been that person who paints in twos. His work sounds gauzy, airquotes perfect, as if he only thinks of comedy and tragedy and nothing in between. When Pressler would say, 'Can you whisper the pain?' Now that is a masterclass.

Indeed the tragic pathos of these variations is heightened more so by the alternation between major/ minor ? (light/ dark) episodes. ( an even more direct reflection of the human condition in fact) A great piece from Mr Denk as usual.