Extended Regret

homage to Reynaldo Hahn

For me the truest summer is late summer, at the brink of too late. For months, wherever I’ve been, the planet has been mass-producing glorious tempting days, which created a kind of moral imperative: you felt you should or even must be on the beach, caressed by a breeze or a person, or parasailing, canoeing, hiking to a glacial lake ... It almost made me angry, how beautiful those days were, and how many there were.

Summer activities often feel infinite-adjacent. You lie by the edge of the sea, you climb a mountain to survey a massive vista and stand inches from plummeting death, you drink an Aperol spritz to slip smoothly into the endless hands of night. Summer pleasures (therefore) shouldn’t have a deadline. It’s silly to try and fit them in between practicing your Fauré piano quartets. You have to stop the clock, and pretend for a while that life is not slipping away, which means you have to believe that what you’re doing right now, this glorious escape at the edge of the infinite, is real life.

In early September, you realize you should have accepted more of those invitations from perfect days, instead of worrying or practicing. You regret your virtue, as much as any sin.

---

In the last moments of summer I tend to go out to the Olympic Peninsula. This year, we played (at my instigation) the Reynaldo Hahn Piano Quintet. The slow movement is one of the most profoundly beautiful pieces in the history of French music.

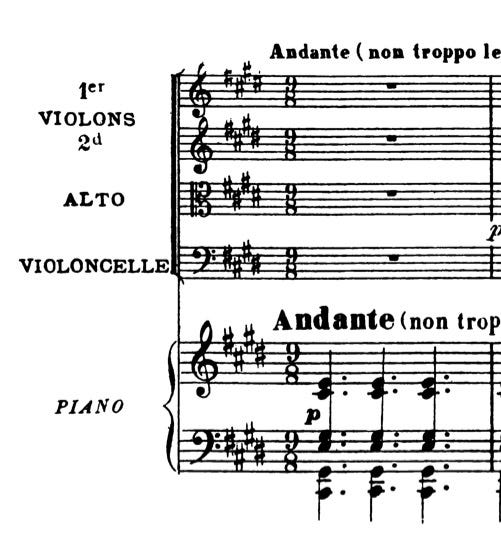

The pianist begins by strumming in the minor key. A heartbeat, a pulse--whatever form of time you want to call it.

What tempo should I play? This question would seem to require a decision, or a metronome mark, but it’s a process. Crucial and mysterious. It starts as an instinct, maybe, then you begin to test your tempo against experience, experiment, against your colleagues’ thoughts, what the composer seems to have wanted. It starts with pure desire, or a thought, an impulse, one of a thousand possible tempos, and then gradually it becomes a certainty that only one tempo will really do. Maybe you start with an idea, yes, I’m pretty sure the speed of this piece “should” be this (like certain insensitive conductors), but then the music appears and you realize your idea has to bend around the notes. Choosing a tempo should be a sensual or emotional experience. What speed allows the music to speak, helps us to hear and receive events, without feeling pushed and without tedium? How do we want time to feel? I recently heard someone play the theme of the Goldberg Variations so slow that it almost killed me.

The cello starts from the main note, rising a fifth, and already we have something to savor, this mildly unnamable chord on the cello’s second measure:

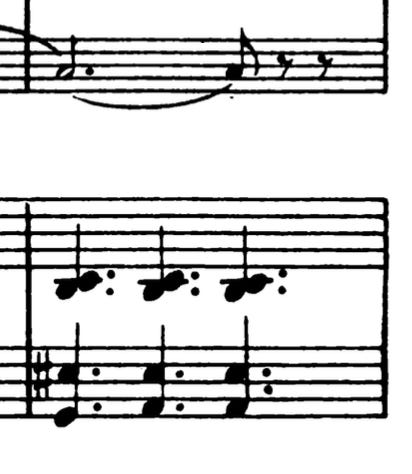

Some French music—let’s be honest—can feel like an exhausting excess of pleasure. One well-lubricated, gorgeous sonority after another, most often seventh or ninth chords. Lovely, yes, but soon you feel you can’t hold on, like when you put on too much lotion and your hand slides off the doorknob. Hahn gives us an antidote to this: a seventh chord with an interesting problem. It’s not officially a seventh chord, it’s just two dissonances stacked on each other, F#-G#, C#-D#, and yet you feel--it could be one. It could so easily be categorizable--just shift one note up or down! And yet, no. The theme of this movement, and all its depth, depends on the resistance of these not-quite chords, which provide a kind of grip.

The cello rises another fifth, and creates a searing dissonance between this peak note (D-sharp) and an A major chord. Aha. We are nurturing a little family of dissonances, sitting on the interface between pleasure and pain.

We fall back to a conventional seventh chord: the typical open-ended end of a first phrase, a musical comma. In a masterstroke, Hahn sidesteps cliché, and complicates the comma, by shifting the piano’s bass up a half-step. We hear first the “correct” chord and then the altered version, with its pained rub against easy meaning:

A delicious paradox: the slightness of this motion vs. the profundity of the effect. For two beats we listen to this rub of the altered seventh chord with its one “wrong” note, we taste the pain and ambiguity against the memory of the “normal” chord, we feel it sensually without (it seems) the intervention of the mind that so often characterizes German music.

The end of the cello melody is another gorgeous pleasure/pain moment. The cello lands on a familiar note—D#. This D# begins its life written as an E-flat, possibly leading to a distant harmony, opening up new vistas. But in its last moment it returns to its origins, and falls back (with a shiver, I’d say) into the melancholy minor of our opening. In performance, a musical cellist creates a little journey of sound on this one note—shifting bowspeed and vibrato, some alchemy of motion, to alter the acoustic appearance of the identical pitch, to make it shimmer. The dissonance melts and re-forms.

This calls to mind of one of my favorite markings in Franck: non troppo dolce. Lovely and sweet, of course, but not too sweet, not cloying, not vanishing or slipping. It suggests a little closet of different beauties—for different occasions. Some with a sharper edge, cutting you like a knife, and other (more melting) beauties like the glance of a finger along your arm. And it is the complicated, often heartbreaking passage from one beauty to the other (even within one note) that is so fascinating to these late Romantic French composers.

—

Staring out at Lake Sutherland, at all times of day, surrounded by trees and moss and ferns, unimaginable profusion. Out the kitchen skylight, an epic pine that could crush you and the house in one blow, but green and inviting, the texture of the looming trunk—somehow you want to cuddle up to it. There is the ever-varying promise of the morning, coming through the mist, and there are the many incomparable slow sunsets, with the gradual appearance of more distant mountains … all of this unbelievable pleasure can’t be separated from regret, from the summer that was.

The second time that Hahn states his theme, the harmonies subtly change. They have become even more lovely—if that were even possible. It would be easy for me to label the chord changes, to force-feed you “the facts,” but far more difficult to explain why or how the memory of the first time haunts you, or how you just know that the harmonies have changed, even if you don’t know exactly how … I’ve played this movement a fair bit and I couldn’t tell you what happens, and I don’t want to look at the music to find out. Not out of laziness. But because the shiver that it produces is about knowing without knowing—a change that passes through you and is not explained.

An interesting moral: as inexorable as this theme appears to be (as life appears to be), you can still take a different path through it.

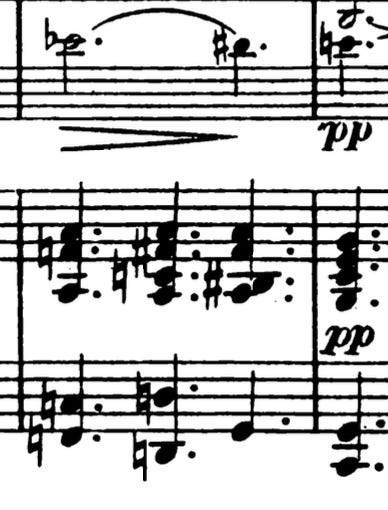

The third time through the theme, the piano ripples in gorgeous fives:

This wave of rhythm rubs against the prevailing three to a bar (a clash of prime numbers), and against the larger eight-bar symmetry, a dissonance of rhythm as painful/seductive as the many chords we have heard.

All of these changes are “development” without the baggage of development, sidestepping its traps, abstaining from annoying sequential equations. It really is to be admired, and you keep wanting it go on, as sad as it is, a kind of delicious extended regret.

—

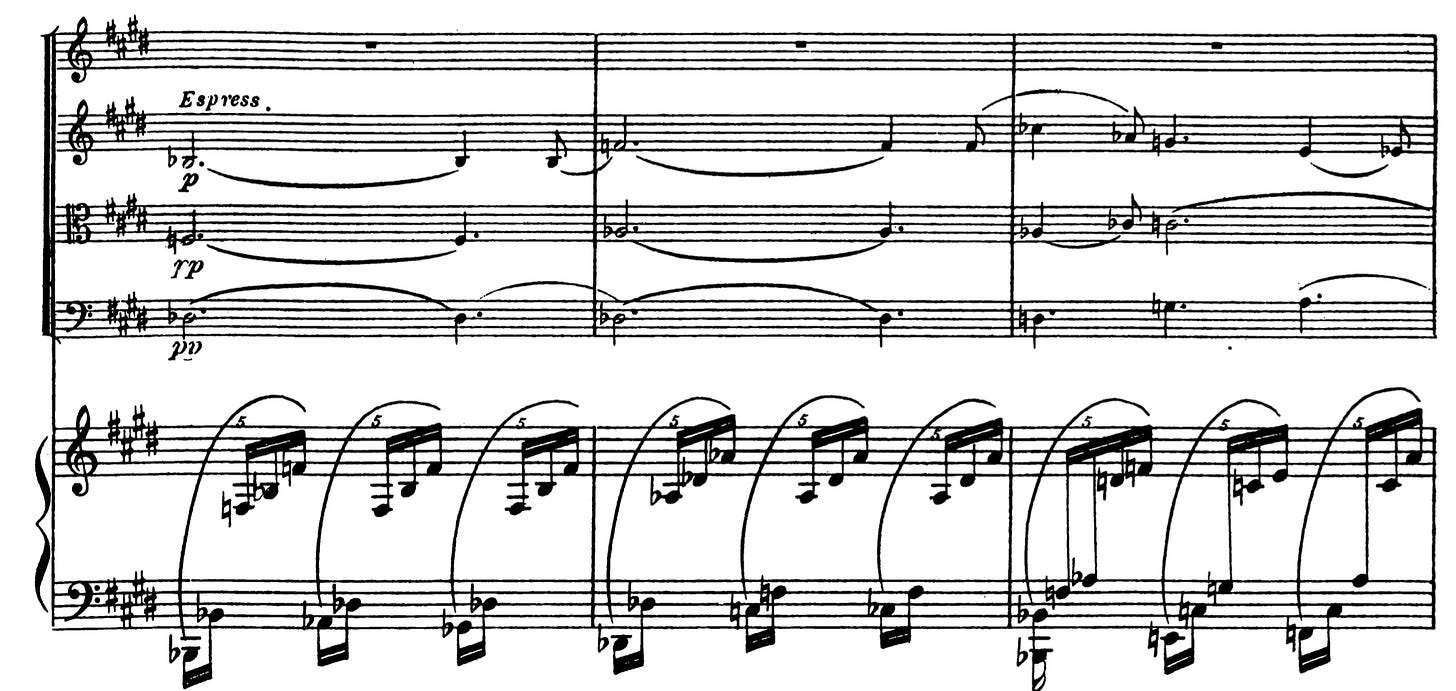

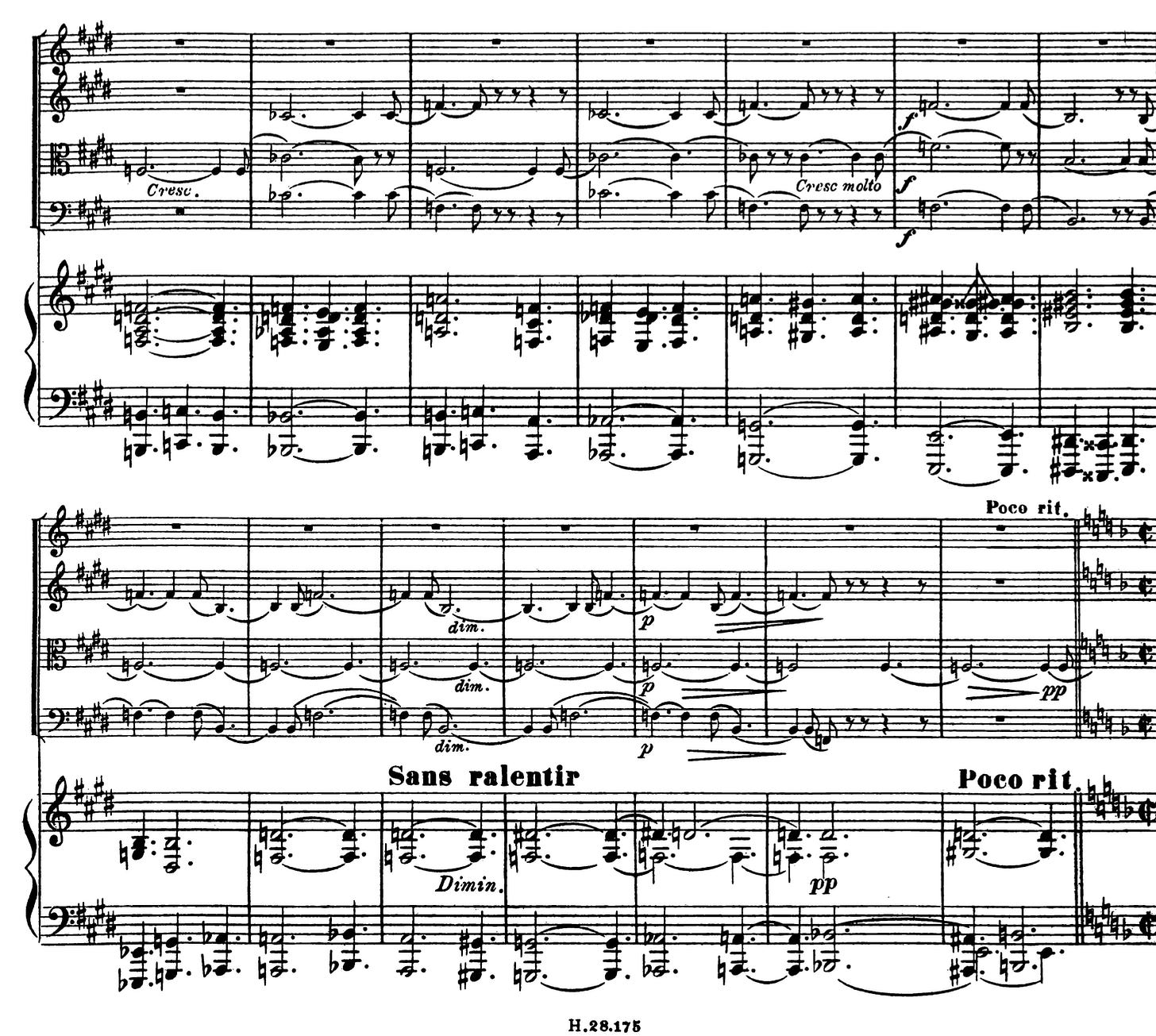

After all the dark unfolding, we reach that most Proustian of narrative events: an impasse. You can see on the page the collapse of the musical story, the piano insisting on various bass lines which don’t seem to go anywhere, the generative rising fifth passing back and forth, unproductively:

If you managed to get through In Search of Lost Time, you are super familiar with those moments, especially in books five and six, when Proust goes in circles, when you can’t bear to hear about *&#(* Albertine again, or whoever or whatever obsession. Dude (you think) maybe even your act of attention is part of the problem, maybe you’ve written yourself into this impasse. Maybe part of the problem is pretending to the world that you have a crush on a woman.

And precisely at the apex of this Proustian disaster, and with the same miraculous sense of knowing and planning (but not pre-ordaining) and finding the one key to unlock the problem and our hearts, the first violinist (silent all the while) manages to come in:

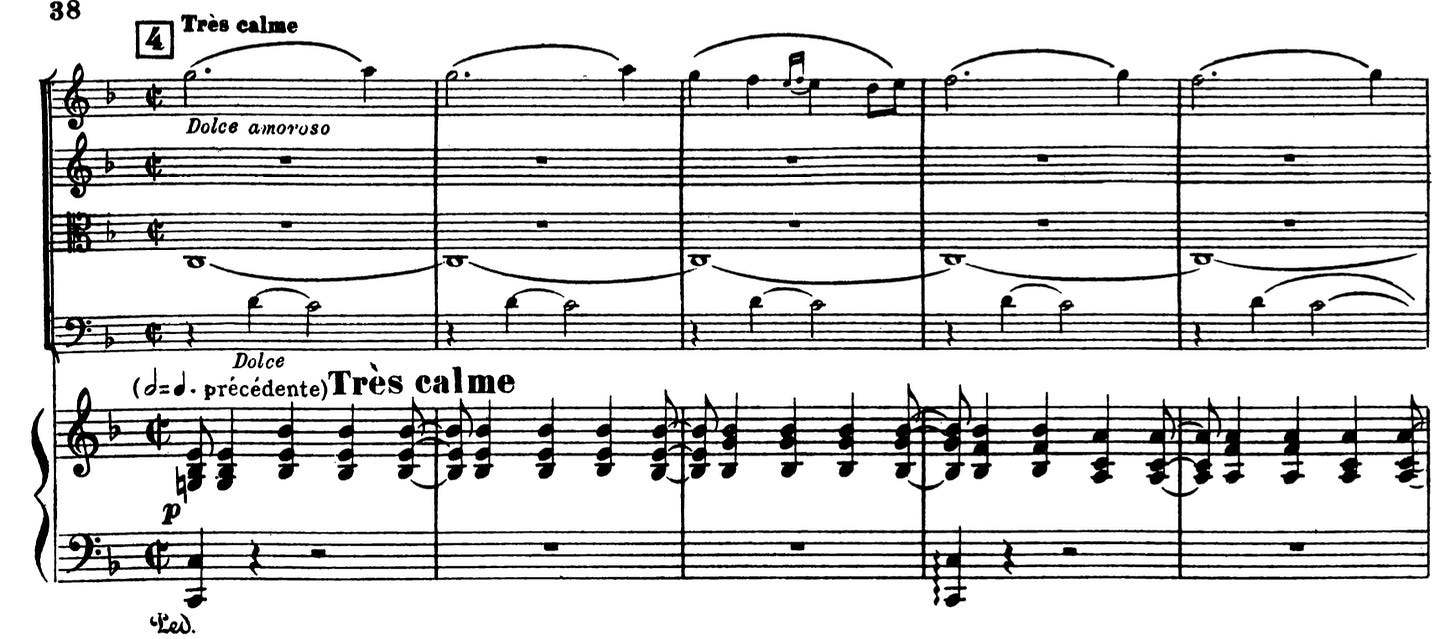

The markings on the page are lovely, as are the pitches. Trés calme, yes, and dolce, again, sweetly—you hardly have to be told. And yet also quite specific about the time relationship. The heartbeat of the old sorrow is the same (slightly disguised) as the syncopated sway of this new idyll.

The math is disguised because the piano is syncopating/palpitating and the cello is replying on the offbeats and nothing about this theme is insisting on its meter, exactly. There is also the little ornament in the melody, blurring the beat, suggesting the sensual, maybe even the erotic. Behind the scenes, you can find two three-bar phrases and then a four-bar. A delicious guiding asymmetry—a proportion you can’t quite hold on to, and you’re not meant to.

A more tender, simple-yet-elusive theme is hardly to be imagined. Pure inspiration and (also) pure craft. It unfolds over a couple pages of the score, and the piano gets its one moment to respond to the theme (which I can’t help milking for all it is worth) … Isn’t so much of French music about creating or re-creating idylls? An idyll has no goal, it does not practice the piano for God’s sake, it merely wants to be, to be left alone or to escape.

—

The main melancholy theme recurs—sigh. We get the sense of a frame, the usual ternary form, darkness framing light.

We are plodding or treading through the melancholy theme again, when Hahn does something marvelous—he brings back the first violin a few more times, with fragments of paradise:

I’m not a huge fan of French combinations of themes. Sometimes it can be ecstatic, I suppose. More often it’s like you’re lounging in Xanadu’s pleasure dome, when your counterpoint teacher bursts in the door. Very few composers can make the academic ecstatic (Bach leaps to mind).

Hahn, luckily, does not really try to combine these ideas—he just interweaves them. The violin remembers the idyll, the rest of the instruments take us back to the sorrow, the violin tries the memory again, more desperately. The harmonies are subtle, and the slow pacing of the interaction, a kind of struggle between worldviews that don’t really want to struggle. It is not a philosophical struggle, like Beethoven—there is no answer. At last the violin wins out (seeming to convince the rest) and we get the idyll again … it doesn’t feel like a victory but a surrender.

What is Hahn trying to tell us? He has offered us two compelling senses of time—one duple, one triple. One treads, another floats. The floating time does not have the complex or deep harmonies of the treading time—but it has other, equally worthy beauties. These senses of time are separated structurally and instrumentally.

Surely you’ve already guessed my metaphor. If the middle section is (let’s say) the beach or some other summer surrender, a perpetual present, the outer section is the real life we are reentering, the semester, the season, the workweek, or whatever your treading reality might be, the profound passage of years, days, hours. Maybe what I find so essential, so moving, is how the music feels torn between them. It is built on the conundrum, organized around the impossibility of reconciling these two faces of time.

Often over my head but always so engaged and engaging. You make it alive for us all.

Given that 'Si mes vers avait des ailes.' and a few other songs were the extent of my knowledge of Reynaldo Hahn, what a surprise to find that he could compose music of such apparent density and visual imagery. I had no idea he wrote amazing chamber music. I listened to the whole quintet performed by Kaleidoscope Chamber Collective (the only recording I could find on Spotify) and will now listen to his other chamber works. Gladly. I've always liked French chamber music and its way of evoking a season, a mood, a landscape, an emotion. Hahn interweaves all these evocations into a lovely, intricate tapestry of sounds that suggests a far greater understanding of music's communicative power than I would have given him credit for. Thanks for this deep analysis, and guide to my second listen.